Digitization, Adversarial Legalism, and Access to Justice Reforms

By

By

Leo You Li[1]*

Abstract

The advent of digital technologies has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of access to justice (“A2J”) worldwide, transforming both how litigation inequality manifests and how states respond. While many countries have embraced new types of systemic reforms—such as cross-agency alternative dispute resolution (“ADR”) platforms, centralized digital case management systems, and tailored judicial data analysis—the U.S. legal system has shown notable resistance. This article argues that this tension is rooted in what Professor Robert Kagan terms “adversarial legalism,” a distinctive American legal culture that relies on private litigation to solve social ills and lawyer-driven adversarial judicial procedures. This legal culture, deeply intertwined with American rule-of-law values, almost equates litigation reliance with separation of powers and adversarialism with due process. It creates strong institutional inertia against the emerging trend of “digital systemic reforms,” which are characterized by their prevention-based, inter-branch, and data-driven nature. Drawing on comparative case studies of the United Kingdom and China, this article argues for a more nuanced understanding of the rule of law as a spectrum—one that allows for the thoughtful incorporation of digital systemic reforms to resolve the A2J crisis while upholding democracy.

It is no longer news that the American civil justice system is facing an access-to-justice (“A2J”) crisis.[2] And yet, the essence of A2J has evolved significantly overtime. For much of modern history, challenges in A2J were largely synonymous with unmet legal needs, focusing narrowly on the lack of legal services for disadvantaged groups.[3] More recently, the A2J crisis has come to reflect deeper social welfare deficiencies that manifest in the court system: financial hardships morphed into debt collection lawsuits,[4] housing instability into eviction cases,[5] and systemic health injustice into a spectrum of family law and healthcare-related litigation.[6] Increasingly, courts have become the “emergency rooms” of social crises, stepping in to cure social ills when legislative and executive branches fail to act.[7] The A2J crisis is no longer merely an issue of legal services but a reflection of pervasive systemic inequalities across society.[8]

Thus, critiques of the A2J landscape today have been fundamentally different from those of decades past. While earlier criticisms largely focused on inadequate legal representation for the poor, today’s conversations probe broader and deeper questions about the justice system itself. In consumer finance, for example, why have courts, as democratic gatekeepers, become “rubber stamps” for predatory debt collectors exploiting vulnerable consumers?[9] Why have administrative agencies failed to intervene with proper oversight and welfare measures before various predatory lending issues escalate to litigation?[10] And, at an even higher level, why is the American justice system, by design, so reliant on courts to resolve social ills that might be better addressed by other public institutions?[11]

This shift in how we understand A2J is as troubling as it is theoretically intriguing. While various cultural, political, and institutional factors have shaped it, two forces are particularly critical: (1) an increasing social digitization process that reshapes dispute resolution, legal professions, and the perception of justice;[12] and (2) a burgeoning comparative awareness that observes American civil justice from a global perspective.[13]

First, digitization, as both a disruptor and an enabler, has pushed American civil justice to a crossroads.[14] One account sees how technology exacerbates social inequalities and manifests them in litigation.[15] This dynamic is particularly stark in the context of high-volume, low-value adjudications such as the debt collection, where technology’s affordances have created profound asymmetries between institutional actors and individual litigants, especially pro se litigants. Advanced legal technologies enable debt buyers and specialized law firms to manage lawsuits at scale, automating repetitive legal tasks to reduce costs and maximize efficiency.[16] However, as many scholars have observed, the efficiency enabled and scaled by technologies are largely captured by institutional actors, while individual litigants remain excluded—“[l]egal tech is lopsided.”[17]

Another view, “techno-optimism,”[18] sees the promising tools offered by technologies to address the challenges noted above. These tools provide an increasingly ambitious spectrum of reform options.[19] Conventional proposals include online dispute resolution and e-filing systems that simplify procedures. Further along the spectrum is using technology to enable judges to play more active roles such as electronic case management platforms.[20] Even bolder proposals include adopting an “adminization” model where administrative agencies act as gatekeepers to manage high-volume disputes before they flood the courts,[21] creating data-sharing systems between courts and stakeholders to examine systemic issues,[22] or allowing AI-enabled practitioners to provide non-lawyer legal help.[23] These reforms are often grouped under the umbrella of “systemic reforms” due to their unconventional ambitions.[24]

Beyond digitization, comparative awareness provides another lens for understanding the A2J crisis, which is not unique for America.[25] Countries across Europe,[26] Asia,[27] and Africa[28] grapple with similar challenges. The global understanding of A2J somewhat parallels the American understanding in that it also experienced several “waves,” from legal aid barriers, diffuse interests between parties, internationalization of human rights protections, digital divides in new technologies initiatives, to systemic race and gender inequality.[29]

While access to justice has been an integral component to the value of the rule of law, what may surprise many people is, while the United States has long exported its rule-of-law values abroad, its own A2J crisis now stands as a counterexample to its purported global leadership in the rule of law.[30] The latest data from the World Justice Project’s 2024 Rule of Law Index reveals that the United States ranks 107th out of 142 countries globally on “accessibility and affordability of civil courts,” behind many wealthy nations and at the bottom among high-income countries.[31] According to the Justice Gap Report, low-income Americans do not receive any or enough legal help for 92% of their civil legal problems.[32] Moreover, those reforms deemed to be the most ambitious in America—such as integrating centralized digital case management systems or establishing cross-agency platforms for alternative dispute resolution—might be the first choice of many other jurisdictions.[33]

Bringing these threads together reveals a complex dynamic between technological change, rule of law, and A2J in a global context. How does digitization reshape the A2J landscape? Why are some new types of systemic reforms in the digital age necessary to address the A2J crisis? Is there an inherent tension between American legal culture and such digital systemic reforms? What lessons can be drawn from global practices? In answering these questions, this article argues that we must move away from a rigid conception of the rule of law as a static ideal. Instead, rule of law is a spectrum, one that allows for greater flexibility in balancing systemic reforms with the foundational values of the American legal culture.

The article proceeds as follows. Part I uses the case of consumer finance, an area where the A2J crisis manifests globally, to conceptualize the dual impacts of digitization on A2J. On the problem side, digital tools intensify the mutual reinforcement of the regulatory and judicial challenges. Legal technologies enable mass litigation, making judges overwhelmed and debtors exploited. Financial technologies magnify regulatory arbitrages and turn litigation into an unjust means to bypass regulation. On the solution side, digital technologies offer courts and regulators mutually beneficial tools to collaborate. Judicial data has the potential to aid regulatory decision-making upon appropriate collection and analysis. Regulators can act as litigation gatekeepers, data sharers, and technical supporters to benefit court operations. The dual impacts of digitization explain why prevention-based, inter-branch, and data-driven systemic reforms are crucial.

Part II draws on Professor Robert Kagan’s theory of “adversarial legalism” to argue that the American legal system has largely resisted systemic reforms on A2J due to its commitment to this unique legal culture, which manifests in two fundamental ways. First, the heavy reliance on private litigation as the primary mechanism for addressing social issues entrenches a fragmented, patchy reform approach that resists systemic reforms such as inter-branch data sharing, unified case management, proactive dispute prevention, etc. Second, the dominance of lawyer-driven, adversarial court procedures elevates procedural formalism but fosters institutional inertia against reforms that emphasize equity, such as ADR, judge-led discovery, AI legal tools, etc.

Part III conducts two comparative case studies on the UK and China to explore how different countries have embraced systemic reforms. The UK case illustrates how digital systemic reforms can align with democratic rule-of-law principles, leveraging inter-branch collaboration and data-driven initiatives to enhance access to justice. China, by contrast, demonstrates how a state-driven, centralized governance model can implement systemic reforms that prioritize social stability and equity, albeit with trade-offs in judicial independence and procedural fairness. The two case studies underscore the adaptability of digital systemic reforms across diverse legal cultures.

The article concludes by advocating for a more flexible understanding of the rule of law—one that unbundles litigation reliance from separation of powers and adversarialism from due process. The American resistance towards digital systemic reforms is a contingent cultural and institutional construct, rather than an inherent requirement of the rule of law. Through a set of political and procedural safeguards, this shift would welcome prevention-based, inter-branch, and data-driven systemic reforms that make justice real in the digital age.

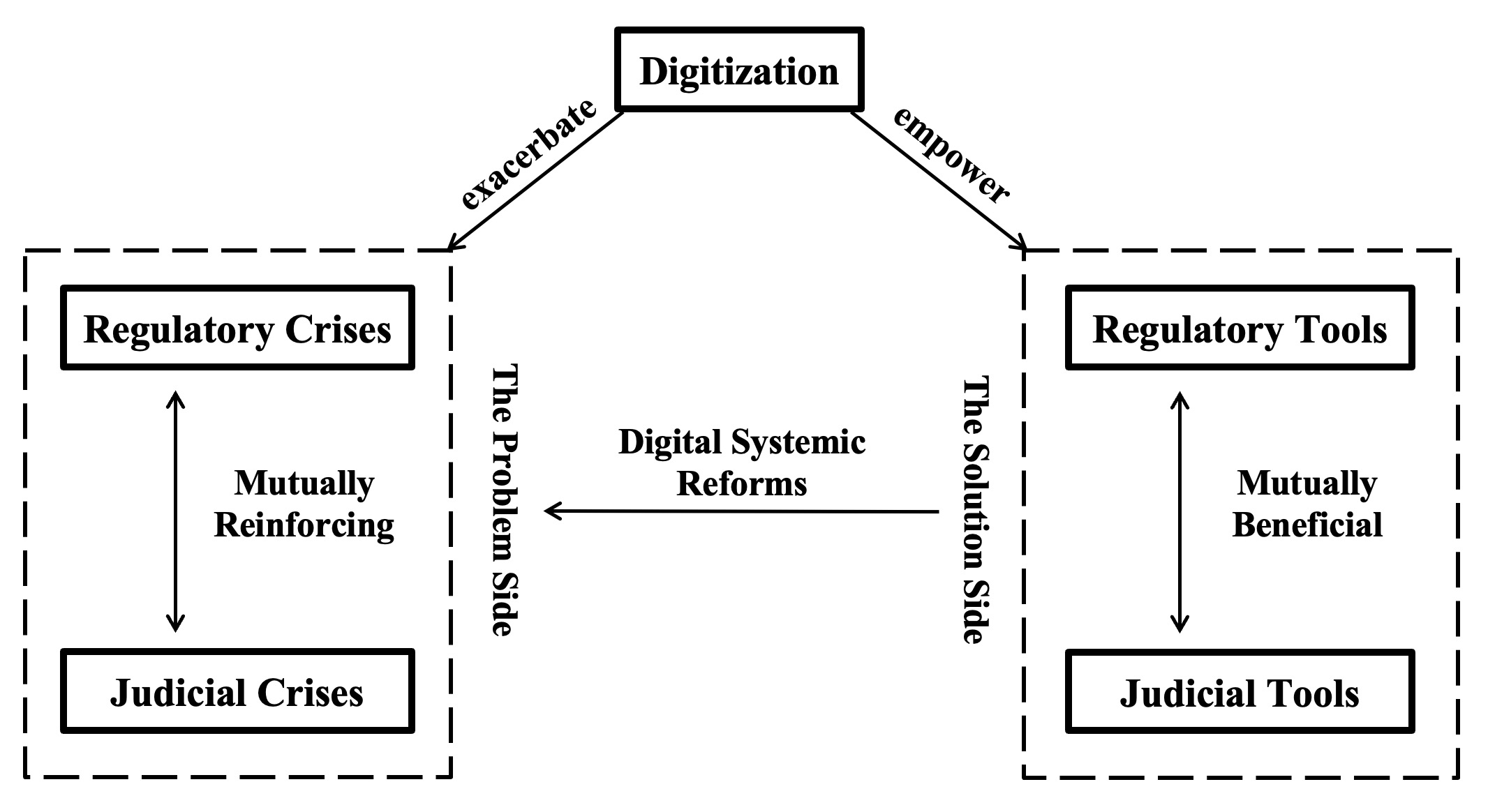

Digitization has dual impacts on the A2J landscape, transforming both how litigation inequality manifests and how states respond. As Figure 1 illustrates, digitization, on the one hand, exacerbates judicial and regulatory challenges; on the other hand, it offers reciprocal toolkits that enable courts and regulators to effectively respond to these issues. These intertwined challenges and opportunities give rise to an innovative type of responses that I term “digital systemic reforms,” characterized by their prevention-based, data-driven, and inter-branch approaches.

Figure 1 The Dual Impact of Digitization on Access to Justice

Digitization has first intensified a “judicial capacity crisis” as financial technologies and legal technologies empower market players and law firms to facilitate massive commercial transactions and initiate high volumes of lawsuits.[34] Financial technologies enable the large-scale lending transactions that underpin industries like third-party debt buying. Meanwhile, legal technologies allow debt collectors to automate litigation processes and file lawsuits at scale with minimal costs.[35] Litigation, in this context, becomes an efficient strategy to recover debts cheaply while realizing substantial profits.[36]

The scale of debt collection operations leveraging financial and legal technologies is striking. Today, randomly browsing a website of a debt collection law firm, advertisements are filled with words like “a high level of automation and litigation flow[]”[37] and “proprietary collection process[.]”[38] These specialized technology systems aim to optimize the time of lawyers by automating documentation gathering, workflow auditing, and error detection. The goal is to secure as many favorable judgments as possible without the need for extensive court motions or appearances. According to the CEO of a collections-litigation software company, such technologies have made litigation the “most effective debt recovery strategy,” as they enable efficient management of high-volume cases.[39] Technology has indeed transformed the debt collection landscape, which makes litigation an integral component of debt recovery processes.

As a result, the volume of debt collection lawsuits, especially those filed by debt buyers against consumers, has surged. Between “1993 and 2013, the number of debt collection suits more than doubled nationwide, from less than 1.7 million to about 4 million,” and now comprises a growing share of civil dockets.[40] Between 2012 and 2017, debt buyers accounted for nearly half of all debt collection filings in the five largest counties in California.[41] Texas has experienced a similar trend as well in that “debt claims more than doubled from 2014 to 2018, accounting for 30% of the state’s civil caseload by the end of that five-year period.”[42] In Michigan, debt collection lawsuits made up 37% of all civil district court case filings by 2019.[43]

Furthermore, most debt collection lawsuits are mostly brought by repeat players. Over the span of two decades, the face value of defaulted debt sold on the secondary market has increased by more than 1500%.[44] From 2009 to 2013, twenty-two debt buyers filed more than 168,000 cases in Maryland.[45] In Michigan, third-party debt-buying companies are responsible for 60% of debt collection filings as of 2019.[46] In California, debt collection cases filed by top debt buyers experienced a short decline after the implementation of California’s Fair Debt Buying Practices Act passed in 2013 but again inched upwards since 2015.[47]

Overwhelmed state courts lack the capacity to effectively manage this influx. Judges are stretched thin and struggle to adequately handle all cases on their dockets.[48] This results in a situation where cases are adjudicated by court clerks and their assistants, and cases do not receive the attention they deserve.[49] Some courts operate “judgeless courtrooms,” where unrepresented defendants negotiate with attorneys in informal settings, with lax evidentiary standards.[50]

The challenges posed by high-volume debt collection lawsuits extend beyond judicial capacity. Regulatory failures, exacerbated by technological advances, create an “insufficient social safety net” that enables abusive practices by creditors and debt buyers.[51] Rather than resolving disputes in good faith, many business creditors exploit litigation as a mechanism to bypass regulations.

With the advent of advanced technologies, consumer financial markets are becoming increasingly “driverless,”[52] with debt collectors finding new avenues to engage in deceptive practices. For example, third-party debt buyers frequently file claims based on “bad paper”—documents that lack sufficient evidence to substantiate the amount allegedly owed.[53] Debt buyers often resort to “robo-signing,” where affidavits are signed without verifying their accuracy, to assert ownership of a debt in litigation without adequate proof.[54] In a two-year investigation, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (“OCC”) found that JPMorgan Chase filed false and improperly signed affidavits in its own debt-collection lawsuits.[55] Additionally, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (“CFPB”) penalized two major debt buyers, Encore Capital Group and Portfolio Recovery Associates, for using robo-signed and false affidavits in 2015.[56] The highly automatic robo-signed tool enables debt buyers and their attorneys to churn out collection lawsuits at an astounding pace.[57] Some law firms even rely on computer systems to decide which accounts to pursue in court, with human attorneys giving the documents only a cursory review and adding their signatures.[58] The CFPB also discovered in 2015 that Chase “filed lawsuits and obtained judgments against consumers using deceptive affidavits and other documents that were prepared without following required procedures.”[59] The CFPB found that “Chase employees signed affidavits ‘without personal knowledge of the signer, a practice commonly referred to as “robo-signing.”’”[60] The CFPB also found that “there were mistakes in about 10% of cases Chase won and the judgments ‘contained erroneous amounts that were greater than what the consumers legally owed.’”[61] Consumer rights attorney Jerry Jarzombek noted that “Chase has all the evidence, and we have to beg to get it[.]”[62]

The case Royal Financial Group, LLC v. Perkins exemplifies these predatory tactics.[63] In that case, Royal Financial Group, a third-party debt buyer, routinely purchased large portfolios of defaulted debt and filed lawsuits against individuals named in the portfolio. But Royal never actually obtained the original credits agreements belonging to those individuals and did not offer any evidence establishing the amount of debt owed. Whenever challenged, the company just dismissed its cases, which reveals its primary purpose was to obtain default judgments rather than collecting debts in good faith.[64]

This vicious cycle—regulatory failures enabling abusive litigation, which in turn strains judicial resources—threatens the legitimacy of the legal system.[65] Nationwide, 29% of white people reported having been contacted about a debt in collection, whereas 44% of people of color reported the same.[66] Black communities are hit much harder by debt collection lawsuits than white ones.[67] In Michigan, two to three times more debt collection lawsuits are filed against consumers in majority Black neighborhoods compared with majority white neighborhoods across all income levels.[68] As our court system has gradually evolved into a “publicly subsidized debt-collection system[,]”[69] its role moves further away from what is known as the “the emergency room of democracy.”[70] Addressing these intertwined crises requires a systemic approach that transcends the capacities of any single institution.

Judicial digitization has transformed courts into hubs of data.[71] Moving beyond their traditional role of adjudication, courts now actively produce, utilize, distribute, and regulate data as a strategic resource.[72] This transformation not only enhances administrative efficiency but also allows courts to play a proactive role in shaping policy responses. By leveraging insights from judicial big data, courts can inform regulatory strategies and help prevent disputes before they arise.[73]

In the context of debt collection, courts can provide regulators with critical tools to identify and combat deceptive practices, such as missing chains of ownership or robo-signing. One example is the court rules and protocols change in New York state, introduced by former Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman in 2014, where debt-owners are required to provide documentation of ownership when filing lawsuits.[74] Following the law change was a significant reduction in debt lawsuits against New York consumers, but debt collectors quickly adjusted again.[75] However, if the underlying issue necessitates broader rule and protocol revisions beyond a Chief Justice’s mandate, the sharing of such valuable information between courts and regulators can help address the access to justice issue effectively.

Several policy proposals have emphasized fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, particularly through data-sharing initiatives between courts and regulatory agencies. One is the data-sharing model between financial regulatory agencies like the CFPB and local courts.[76] The CFPB has accumulated national data on unscrupulous debt collectors, which can significantly aid problem-solving judges in addressing information asymmetry. Meanwhile, local case data would enrich the volume of information maintained by the CFPB, which is currently limited to consumer complaints and examinations of financial institutions conducted by the agency.[77] Professor Steinberg suggests the establishment of reciprocal communication channels between courts and the CFPB to enable an informational feedback loop, facilitating interdisciplinary collaboration.[78] By effectively utilizing, producing, and disseminating data, courts are evolving into “data facilitators” that can make unparalleled contributions to the otherwise separate regulatory side.

Angela Tripp, who served as vice chair of the Michigan Justice for All Commission that issued a report on debt collection, called on “other branches of government” to jointly take action to tackle the access-to-justice crisis in debt collection lawsuits.[79] Courts, while central to this effort, are neither technological experts nor necessarily equipped to attract top tech talent. Despite their strides in judicial digitization, courts often lack the capacity to develop and manage technological solutions independently. This necessitates coordination between internal judicial administration and external governmental support.

For example, in terms of Online Dispute Resolution (“ODR”) system constructions, the Joint Technology Committee (“JTC”) of state courts has recommended that courts deepen their collaboration with different stakeholders, including relevant agencies in other branches of government, across all aspects of ODR development, from technical design and funding acquisition to ongoing system maintenance.[80] At the federal level, courts have also increasingly recognized the value of input and support from non-judicial actors, including government agencies, in improving electronic infrastructure and digital service delivery.[81]

Another, more advanced model is called “adminization.”[82] This approach places an agency as a gatekeeper between consumers and debt collectors tasked with investigating and finding wrongful behaviors before they reach court.[83] The agency will be notified of every incoming lawsuit, then select a sample of cases to audit, detect potential fraud, and levy fines against any offenders being inspected.[84] In addition, machine learning and algorithmic analysis could be used to improve the accuracy of the selection process by focusing on the cases that are statistically most likely to involve wrongdoing.[85] Adminization has the potential to deter the initial filing of wrongful suits, reduce the volume of claims overall, and free up the courts to scrutinize more closely on other cases.[86] Compared with its alternatives, this approach is also “budget-friendly” and “political[ly] feasible[]” compared with its alternatives.[87]

In sum, the complementary roles of regulators and courts highlight the potential for a more integrated, collaborative approach to tackling A2J challenges. The courts can transcend their traditional adjudicative role by leveraging their position as data facilitators, while regulatory agencies can enhance judicial processes by acting as gatekeepers, data sharers, and technical supporters.

The intertwined regulatory and judicial challenges, coupled with the reciprocal regulatory and judicial toolboxes, highlight the urgent need for systemic reforms to promote A2J. These reforms span a broad spectrum, from inter-branch data sharing, agency being gatekeepers, to “adminization” initiatives. We can further summarize three key features of systemic reforms in the digital age, by their aim, subject, and means.

First, this type of reform prioritizes prevention-based solutions that transcend resolving individual disputes. Their goal is not merely to adjudicate cases but to mitigate legal risks before they arise and even address the root causes of systemic issues.[88] For example, pre-litigation mediation programs have the potential to resolve disputes before they escalate into formal lawsuits. These programs often use digital platforms to facilitate communication and agreements between parties, which reduce the burden on courts.[89] Another example is the use of risk assessment calculators, which leverage advanced algorithms to help potential litigants identify possible litigation outcomes, their legal vulnerabilities, and even actionable recommendations to avoid future similar disputes.[90]

Second, this type of reform relies on inter-branch efforts that integrate the resources and expertise of courts, legislatures, executive agencies, and other institutions into a collaborative network. These collaborations create a more holistic approach to addressing systemic challenges. For instance, the data-sharing model between financial regulators and courts allows agencies to monitor patterns of misconduct in high-volume litigation, such as debt collection cases, while also enabling courts to access regulatory insights to enhance their decision-making. The agency gatekeeper mechanism goes a step further, positioning agencies as intermediaries that filter and review cases before cases reach the courts. This approach not only reduces judicial workload but also ensures that frivolous or abusive lawsuits are addressed administratively. The concept of “information loopback” for law changes, where courts share aggregated data and trends with legislatures to inform regulatory updates, illustrates how systemic reforms can create a feedback loop that continuously refines the legal framework.

Third, this type of reform under digitization is largely data-driven. They leverage digital technologies, centralized management platforms, and advanced analytics to enhance transparency, guide decision-making, and pinpoint when and where rule changes are most needed. For example, centralized case management systems allow courts to track and analyze case trends across jurisdictions, enabling more efficient allocation of resources and identification of systemic inequities. Similarly, judicial data analytics can reveal patterns of bias or inefficiency, providing a foundation for targeted interventions. Advanced analytics can also predict case outcomes and identify high-risk cases, enabling courts and regulators to prioritize their attention effectively. In the debt collection context, such systems can identify repeat offenders or patterns of predatory behavior, facilitating earlier intervention by regulators.

These three features—prevention-based aims, inter-branch nature coordination, and data-driven means—reflect the distinction of systemic reforms in the digital age. The challenge of implementing these reforms lies partly in the technocratic domain and partly in normative resistance.[91] While technological advancements have simplified the technocratic hurdles, normative barriers remain entrenched. The gap between the institutional possibilities envisioned by scholars and the reality of what have been accomplished underscores that the United States has struggled to adopt digital systemic reforms to promote A2J.

This Part adopts Professor Robert Kagan’s theory of adversarial legalism[92] to illustrate a potential American way of resistance to digital systemic reforms on the A2J crisis articulated above. Professor Kagan defines adversarial legalism as “policymaking, policy implementation, and dispute resolution by means of party-and-lawyer-dominated legal contestation.”[93] By contrast, in many developed countries, there is a system of “bureaucratic administration, discretionary judgment by experts or political authorities, informal negotiation or mediation, and the judge-dominated style of litigation[.]”[94]

Two distinctive features of adversarial legalism are particularly relevant here. First, comparatively, the United States relies more heavily on litigation as a method to address social ills.[95] This reliance is often characterized by the notion of the “litigation state,” in which high-profile, complex policy disputes are resolved through a patchwork of lawsuits rather than through coordinated administrative action.[96] But what is more pertinent to our analysis here is how litigation functions in routine, high-volume cases. In these instances, repeat players—typically affluent business organizations—are uniquely positioned to exploit the adversarial legal structure.[97] These well-resourced actors regularly use adversarial legalism to their advantage to undermine the mobilization of antidiscrimination and consumer protections.[98] Thus, whether by design or circumstance, courts become enmeshed in social issues related to consumer protection and regulatory law.

Second, American legal processes—particularly within the civil justice system—are predominantly lawyer-centric rather than judge-led.[99] Over a century ago, Roscoe Pound described the American legal system as reflecting a “sporting theory of justice.”[100] This metaphor aptly encapsulates an adversarial model in which litigants and their attorneys control the framing and presentation of evidence and arguments, whereas judges shoulder more neutral and adjudicative roles.[101] By contrast, many civil law jurisdictions favor judge-led inquisitorial (or quasi-inquisitorial) methods and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, such as mediation and arbitration, that emphasize substantial justice and problem-solving.[102]

A reliance on litigation and an adversarial legal culture is deeply rooted in the rule-of-law values of American democracy.[103] Litigation reliance reflects commitment to separation of powers and an “individualist and antistatist orientations.”[104] Adversarialism has long been heralded as a hallmark of democratic justice,[105] due process,[106] individual dignity,[107] and the free market.[108] As Professor Damaska notes, “the adversary system provides tropes of a rhetoric extolling the virtues of liberal administration of justice in contrast to an antipodal authoritarian process.”[109]

I argue that the United States has largely resisted digital systemic reforms on A2J due to its commitment to adversarial legalism, which manifests in two fundamental ways. First, the heavy reliance on private litigation as the primary mechanism for addressing social issues creates a paradox: although courts and judges are expected to balance competing rights (for example, creditor versus consumer rights in debt collection lawsuits), they often lack both the motivation and the institutional resources to address underlying structural inequalities effectively. Consequently, responses by front-line judges to the A2J crisis remain confined to incremental, patchwork measures within the judiciary rather than evolving into broader, inter-branch systemic reforms. Second, the dominance of lawyer-driven, adversarial court procedures elevates procedural formalism and reinforces institutional inertia, thereby impeding the adoption of reforms that emphasize equity and systemic change.

To start with, a growing number of empirical studies based on in-depth interviews with judges have revealed that many judges view their role as resolving individual cases, one at a time, rather than addressing the systemic issues underlying those disputes.[110] As Professors Shanahan et al. document in their fieldwork, judges often see themselves as neutral arbiters rather than social service providers or systemic problem-solvers.[111] In one instance documented by Professor Rostain’s fieldwork, a judge acknowledged an interest in using data to uncover systemic patterns of bias in court decisions but maintained that her role was strictly to “decide each case on its own merits, one at a time.”[112]

Even when judges attempt to move beyond mere case-by-case adjudication, they frequently lack the institutional tools necessary for meaningful systemic reform. Shanahan et al. found that courts have occasionally introduced ad hoc “institutional innovation[s]” to address unmet social needs left by the inaction of executive and legislative branches.[113] For example, state courts have created new mechanisms outside traditional dispute resolution, such as experimental housing courts to address eviction crises.[114] Individual judges have also made situational decisions, such as refusing to issue protective orders when the lack of affordable housing means the defendant would become homeless, or issuing narrowly tailored orders in family law cases due to the absence of adequate addiction treatment programs.[115] In the absence of social provisions by other branches of government, judges have developed a patchy, under resourced role as a de facto provider of social services by “creating or changing law—in individualized, unwritten ways—to meet litigant needs. . . .”[116]

This intra-court, case-based approach of reforms has significant limitations. For instance, courts’ efforts to address litigants’ broader needs are often based on individual initiatives rather than coordinated experimentation as if a public policy is to be introduced, so it might be ineffective. Further, a judge might rely on his or her own personal networks to refer a litigant to social services, while such efforts can be inconsistent across different systems and without any assurance of realization.[117] In fact, these piecemeal efforts are, at best, just sufficient to resolve immediate disputes at hand but benefit little to the deeper structural A2J crisis.[118] Worse still, piecemeal judicial actions can create a false impression that systemic issues are being resolved, potentially discouraging other branches of government from allocating additional resources.[119]

Beyond the lack of institutional mechanisms for inter-branch, prevention-based efforts, courts are also constrained by financial limitations. Comparative data indicate that, largely due to the structural independence of the judiciary and the commitment towards private enforcement, government investment in civil legal services is significantly lower in the United States, both in absolute terms and as a proportion of national income, with other democracies like the UK, Sweden, and Canada spending several times more per capita.[120] Many U.S. state courts depend heavily on litigation fees for revenue, which creates perverse incentives to prioritize high-volume adjudications, such as debt collection lawsuits.[121] Some courts even charge defendants exorbitant fees simply to respond in civil cases, which further impedes access to justice for consumers.[122]

Meanwhile, data-driven systemic reforms, such as centralized case management systems or digitized tools to identify systemic inequities, require substantial financial investments. Modernizing state and local court technology infrastructure would likely cost hundreds of millions of dollars, resources that may be difficult to secure without significant federal support.[123] Despite recent efforts on court digitization,[124] meaningful investment in civil justice data collection remains slow, hampered by legal, political, and cultural barriers at federal and state levels.[125] One notable example is the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ funding of the Federal Justice Statistics Program (“FJSP”). Under the direction of the Urban Institute, the FJSP developed a dyad linking system that aggregates records from multiple data sources, enabling the tracking of person-cases throughout the federal criminal legal system.[126] But creating this data structure has proved extraordinarily challenging, as evidenced by the Urban Institute’s sixty-six‐page report.[127] Moreover, the system is confined to the criminal domain and depends on successfully linking data across at least two agencies. Extending such an approach to integrate both civil and criminal systems—which employ markedly different data collection methods—would likely be even more difficult.[128]

In sum, these institutional constraints create a paradox that prevents American courts from fulfilling their potential as agents of systemic reform. While judges are often aware of underlying structural problems, they lack both the motivation and the resources to address systemic inequality effectively. This gap urges us to reconsider deep institutional questions regarding the separation of powers and to ask whether the contemporary role of courts truly aligns with the democratic aims that adversarial legalism was originally intended to serve.[129]

A substantial body of literature contends that the adversarial legal culture in U.S. civil justice undermines A2J. In Kagan’s words, a civil justice structured by adversarial legalism is characterized by “costliness, unpredictability, injustice, and inequality.”[130] This system amplifies the advantages of “repeat-player” litigants over “one-shotter” litigants, both within the litigation process and in strategies to bypass the formal court system altogether.[131] Empirical studies further reveal that the procedural formalism of civil courts, which is largely a by-product of the adversary system, can retraumatize litigants and disproportionately harm vulnerable parties.[132] By contrast, “more hierarchical and judge-dominated system[s]” elsewhere tend to mitigate disparities in legal capacity between parties to a greater degree.[133]

Building on this literature, this article further contends that the commitment towards adversarialism not only exacerbates A2J challenges but also resists systemic reforms aimed at prevention-based, inter-branch, and data-driven solutions. First, adversarialism inherently conflicts with prevention-based and inter-branch efforts. Throughout the 20th century, several reform initiatives in America sought to replace litigation with alternative problem-solving mechanisms but were met with substantial resistance.[134] One such effort was the proposal to divert routine bankruptcy cases from federal courts to an administrative agency during the 1970s.[135] This reform aimed to process straightforward cases more efficiently through specialized staff and non-adversarial methods, addressing court backlogs and reducing costs for debtors and creditors alike. This reform sought to shift bankruptcy resolution away from the lawyer-driven, case-by-case approach. However, it faced strong resistance from bankruptcy judges and lawyers, who feared diminished roles.[136] Broader concerns about the expansion of federal bureaucracy and the potential for inefficiencies in administrative systems further compounded the opposition.[137]

From another perspective, the California Industrial Accident Commission (“IAC”), initially designed as an informal, non-adversarial problem-solving agency for injured workers but later evolved into an adversarial system, also illustrates the strong inertia of adversarialism.[138] The IAC’s creation was first a rare success of systemic reform that circumvented the adversarial litigation system to provide accessible and efficient remedies. However, as Professor Nonet traced the IAC’s progression, he discovered it evolved from a welfare agency with broad discretion in policymaking into a relatively passive arbitrator of industrial accident claim disputes.[139] He describes this shift as a movement from “administration to adjudication,” driven in part by organized efforts of the legal profession, particularly the bar, which sought to introduce adversarial elements into the commission’s proceedings.[140] The IAC’s transformation reflects the pervasive influence of adversarialism, even within systems designed to function outside its framework.[141]

More recently, significant resistance has emerged against non-lawyer providers, such as legal tech companies, seeking to democratize legal services.[142] For example, a recent proposal in Washington State to relax rules on who can deliver legal services exemplifies this tension.[143] The pilot initiative seeks to allow approved companies and organizations outside the traditional law firm structure, to practice law using innovative business models and technology.[144] Proponents argue that this could make legal services more affordable and accessible to underserved populations.[145] However, critics—many from the legal profession—warn that this could erode ethical safeguards, prioritize profits over client interests, and compromise the quality of legal advice.[146]

That said, there are ongoing efforts to ease this lawyer-centric adversary system. In 2020, the Supreme Court of Utah introduced a groundbreaking reform by relaxing the professional rules prohibiting non-lawyers from sharing ownership in law firms.[147] Through a regulatory “sandbox,” Utah now permits alternative legal businesses, fostering innovation in delivering legal services.[148] Arizona implemented a similar reform in 2021, paving the way for more states to follow.[149] However, these initiatives continue to face vocal opposition from critics who express concerns over potential ethical violations, professionalism, and the prioritization of profit over public good.[150] This backlash highlights a broader reluctance within the lawyer-centric system to embrace models that democratize legal services.[151]

Resistance to systemic reforms is not limited to lawyers. Judges, most of whom start their careers as lawyers, often view themselves as passive adjudicators rather than active problem-solvers. Judicial ethics rules, such as Canon 3B(7) of the California Code of Judicial Ethics, prohibit judges from independently investigating facts in a proceeding, even when such investigations could illuminate systemic patterns or abusive behaviors.[152] These restrictions limit judges to adjudicating cases “one at a time” and impede efforts like centralized case management systems that could address broader trends but might constitute ex parte communication. Thus, judges who wish to advocate for systemic changes by actively addressing imbalances of power or providing accessible explanations of legal terms for unrepresented individuals could face limitations due to ethical rules designed to maintain judicial impartiality. As noted by Michigan Chief Justice Bridget McCormack, while judges have unique experience with the flaws in the legal systems over which they preside, ethical constraints limit the form of their advocacy.[153] Effective law reform depends on judges’ contributions, yet they must navigate these ethical boundaries carefully to avoid overstepping their roles.

In sum, while pockets of progress exist, the resistance to systemic reforms driven by the entrenched interests of the legal profession—whether from lawyers wary of losing control or judges constrained by entrenched ethics rules—demonstrates the depth of the adversarial system’s reluctance to adopt digital systemic reforms that have the potential improve A2J.

This Part examines how digital systemic reforms, resisted by the American legal system, have been implemented in two contrasting jurisdictions: the United Kingdom and China. The two jurisdictions are chosen as they represent two distinct approaches to addressing A2J challenges. The UK legal system shares key democratic principles with the United States, particularly its common law tradition, adversarial system, and the doctrine of separation of powers, but in a less extreme way.[154] The UK’s experience can illustrate how digital systemic reforms might be reconciled with similar rule-of-law principles that underpin the American resistance. China, alternatively, operates within a fundamentally different legal culture, characterized by its state-driven, centralized governance model, often referred to as “rule by law” or “authoritarian rule of law.”[155] In this system, courts are deeply embedded within the state apparatus and work closely with other state branches on broader social issues.[156] Judges see themselves as not only facilitators of dispute resolution but also as social problem solvers. Thus, China’s experience illustrates how systemic reforms can address A2J issues when the constraints of separation of powers and litigation due process are weaker. It also highlights the potential costs of such an approach, in particular the compromise of judicial independence and procedural fairness. Together, the two case studies demonstrate that digital systemic reforms are not confined to any single legal tradition but instead reflect how different institutional values shape the tradeoffs that legal systems are willing to accept.

At the center of the UK’s efforts in promoting access to justice is an executive agency named HM Courts and Tribunals Service (“HMCTS”) responsible for administering the courts and tribunals system.[157] Unlike the sharp separation between the judiciary and other government branches in America, HMCTS serves as a “bridge” that connects the Ministry of Justice (“MoJ”), the judiciary, and other stakeholders.[158] A2J initiatives in the UK have been described as a “shared endeavor,”—with the MoJ providing the policy and legislative framework, the judiciary ensuring a balance between open justice and proper administration, and HMCTS managing court operations to promote equitable outcomes.[159]

In recent years, the HMCTS has embraced a data-driven strategy that recognizes data as “strategic assets” to deliver better access to justice.[160] Backed by £1.3 billion initiative, the HMCTS Reform Program has supported a wide range of new projects, including integrated case management platforms and digital court services, aimed at improving the efficiency and accessibility of the justice system.[161] Data First is one of the key projects of this reform.[162] Led by the British Ministry of Justice and funded by Administrative Data Research UK (“ADR UK”), this project is an ambitious data-linking program aimed at making court data available on an open, shared, and secure platform.[163] The general idea is that court data will be securely deposited on the Office for National Statistics Secure Research Service (“ONS”), a government agency that facilitates cross-institutional research. This enables HMCTS to safely share de-identified datasets with other government agencies without hindering personal privacy.[164] The project “provides methods to link data about individuals across these justice datasets, but also with education and social data external to the justice system.”[165]

Moreover, the court datasets are linked with datasets from other government services. Since August 2020, HMCTS has authorized the sharing of ten years of magistrates’ court data and seven years of Crown Court data with the ONS.[166] As of 2024, the platform has published data on civil courts, family courts, probations, among others. This platform allows researchers, court administrators, and government officials to securely access de-identified datasets and to investigate systemic patterns on how justice system users interact with other public services.[167]

To ensure responsible data sharing and access, HMCTS has established a Senior Data Governance Panel (“SDGP”) in partnership with the MoJ and the judiciary.[168] This panel brings together members of the judiciary, civil servants, and independent academics to provide oversight on contentious data-sharing issues.[169] In January 2023, this panel has been formed with five senior officials from HMCTS and MOJ, five senior judges, and at least five independent experts to offer independent expert advice and guidance on the access to and use of court data.[170]

In addition to working with government agencies to build and safeguard an open court data infrastructure, HMCTS also commits to collecting and analyzing data on its own to evaluate the A2J landscape. The Assessing Access to Justice in HMCTS Services report reflects this commitment.[171] Launched in 2023, this project combines a wide range of data sources, including management information on case volumes and timeliness, user characteristics such as sex and ethnicity, service-specific data such as probate grants, user contact information through calls and surveys, and external resources such as UK census data and accessibility tests.[172] By linking user-level data (e.g., ethnicity and age) with court-level data (e.g. case outcomes), HMCTS has announced an intention for the UK to become one of very few jurisdictions capable of assessing A2J through an equity lens by identifying how case outcomes differ by user characteristics.[173]

This A2J assessment project has significantly enhanced our understanding of the A2J landscape in small claim disputes including consumer finance. For example, the 2023 and 2024 reports have conducted comprehensive analysis of data from Online Civil Money Claims (“OCMC”). Launched in 2018 as part of the HMCTS Reform Program, OCMC enables claimants and defendants to manage civil money claims online efficiently.[174] The OCMC service initially focused on claims involving unrepresented litigants for amounts under £10,000 but has since expanded its scope. Since November 2023, legal representatives can issue claims up to £25,000 against unrepresented defendants.[175]

The reports revealed persistent challenges in the UK similar to those in the United States, particularly regarding the low engagement of defendants. Between 2020 and 2023, approximately 70% of cases received no formal response from defendants.[176] But the introduction of OCMC has shown promising results. A March 2025 report indicated that more users are engaging with the system now—“more defendants are responding to claims and . . . more parties are settling without needing court intervention.”[177]

The reports also identified regional disparities and equity concerns in small claim disputes that particularly affect ethnic minority users.[178] The reports highlighted that courts in London and the South East of England, regions with higher proportions of ethnic minority populations, experienced disproportionately slower case processing times.[179] When ranked by the average number of days taken to reach a first full hearing, eight of the bottom-performing courts were located in these regions.[180]

Understanding these issues, the HMCTS further conducted extensive qualitative research involving more than a hundred in-depth interviews. Through this, the HMCTS identified several key barriers to defendant engagement. These include limited legal consciousness among defendants, financial hardship, and delays in receiving paperwork, with some individuals unaware of claims until judgments were issued against them.[181] The study also uncovered additional challenges such as stress and anxiety due to unfamiliarity with the legal system, power imbalances in certain cases, and difficulties in self-representation.[182]

To address these barriers, HMCTS has implemented targeted reforms. Court staff are to simplify and personalize communications to ensure litigants understand the benefits of responding to claims, and courts will work with other government agencies to provide support for individuals experiencing financial hardship. A specialized working group comprising judges and HMCTS administrators has also been established to resolve delays that disproportionately affect ethnic minorities.[183]

That said, the data analyses presented remain cursory compared to the most rigorous academic studies. Nevertheless, the achievements are impressive given the inter-branch collaboration among HMCTS, the judiciary, the Ministry of Justice, and other public institutions in building a robust data infrastructure to promote access to justice. The systemic nature of these reforms allows justice administrators to move beyond isolated case-level or user-level observations and to tackle broader patterns of social inequality. In this sense, HMCTS acts as an “information channel” between the judicial and executive branches.

While these efforts are promising, they also raise critical questions about how to balance systemic reforms with the rule-of-law values of judicial independence and due process. To navigate this tension, the UK has implemented a combination of technological and procedural safeguards that ensure systemic reforms can progress without undermining core principles of justice. On the technological front, HMCTS employs advanced data-sharing frameworks, most notably the ONS “5 Safes” model, which is designed to secure and ethically manage access to de-identified court data.[184] By linking datasets across various systems, such as magistrates’ courts, Crown Courts, and probation services, the framework facilitates inter-branch collaboration while maintaining rigorous controls over sensitive information to safeguard privacy and judicial independence.

Procedurally, HMCTS has established mechanisms to ensure accountability and oversight in its reform initiatives. The Senior Data Governance Panel, which comprises judges, officials, and independent experts, plays a vital role in managing contentious issues surrounding data access and sharing.[185] Furthermore, judges contribute directly to shaping systemic reforms through their representation on the HMCTS board.[186] This structure ensures that systemic reforms respect judicial independence and procedural fairness. Additionally, the UK’s court reforms are subject to independent audits that assess their financial and operational effectiveness. For instance, a 2021 report by the National Audit Office revealed that the expected savings from the HMCTS Reform Programme had significantly decreased, which casts doubt on the program’s financial viability and efficiency.[187] In 2023, an investigation by the National Audit Office found that 55% of divorce cases could not be completed on the digital service.[188] This required manual interventions, undermining the experience of users and threatening the business case for the reforms, which were predicated on an end-to-end digital service.[189] These audits not only highlight areas for improvement but also reinforce transparency and accountability of court reforms.

In sum, the UK demonstrates a pragmatic approach to systemic reforms, combining inter-branch collaboration, robust data infrastructure, and institutional safeguards to enhance access to justice. HMCTS’s bridging role not only enables sufficient funding from the central government but also provides a system-wide perspective that prioritizes data-driven initiatives.

While the UK case study demonstrates how systemic reforms can be carried out through a single new agency that bridges traditionally separate branches of government, China offers an alternative approach within a more state-centric regime. Rather than relying on one new institutional entity, China’s reform strategy operates through a coordinated network of courts and government agencies, where cross-branch cooperation, equity-based judicial decision-making, and rapidly advancing judicial digitization become hallmarks of reforms.

Although the term “access to justice” does not have a direct equivalent translation in the Chinese context, the judiciary has long prioritized making its services more convenient, efficient, and transparent.[190] The revision of the Chinese Civil Procedure Law in 2012 shows an unprecedented commitment to access to justice.[191] A frequently cited statement by Chinese President Xi Jinping underscores this emphasis: “We [must] . . . strive to make people feel fairness and justice in every judicial case.”[192]

The Chinese judicial system also faces similar A2J challenges brought by a high volume of small-value lawsuits, including debt collections. Civil justice in China in general has witnessed an increasingly litigious society in the past decade.[193] According to the 2024 Chinese Supreme People’s Court (SPC) Work Report, the total number of cases handled by Chinese courts has increased by an average of 13% annually since 2013, rising 2.4 times over ten years. The average number of cases handled per judge rose from 187 in 2017 to 357 in 2023—more than one case every calendar day.[194]

Much like the situation in the United States, a notable portion of the high-volume dockets arises from strategic litigation. Many consumer debt cases are brought by underregulated moneylenders—often operating under the guise of fintech platforms—who strategically turn to litigation as a mean to bypass financial regulation.[195] In one Beijing trial court, for instance, a single unlicensed moneylending firm filed 1,395 lawsuits in 2016 alone.[196] Similar tactics have also been observed in mass low-value intellectual property cases.[197] Similar to their United States counterparts, these actors frequently exploit legal loopholes by leveraging superior legal resources and targeting unrepresented defendants. [198] These practices have triggered broader concerns over social stability.[199]

The Chinese approach to promote access to justice is thereby rooted in a recognition that it is not only a pragmatic issue but also a critical source of social stability and political legitimacy. A2J reforms are tightly integrated with the country’s sweeping court digitization initiatives.[200] Enabled by the state’s use of judicial data as tools to enhance social governance,[201] China has adopted a lifecycle approach to navigate A2J, from where civil justice entanglements originate, how disputes are addressed in court, and how to prevent their recurrence in the first hand.

In sections below, I introduce some key examples from the pre-litigation to post-litigation stages, including the digital ADR mechanism, centralized case management system, automated adjudicative tools, and tailored judicial data analysis. Together, these measures illustrate how China’s systemic reforms leverage prevention-based, inter-branch, and data-driven tools to prioritizing equity and social stability over strict legal orthodoxy.

China exemplifies the scholarly observation that “countries less wedded to adversarialism” have found it easier to develop “alternative, non-litigation-based . . . approaches to dispute resolution” that benefit to the public as a whole.[202] President Xi has urged the court system to “put[] non-litigation dispute resolution mechanisms in the forefront.”[203] ADR systems that divert cases from the formal court system have a long history in China.[204] Online dispute resolution (“ODR”) in China was first adopted by e-commerce platforms to resolve small-volume disputes between online sellers and consumers.[205] Then, the Chinese government started investing substantial resources to explore how ODR technologies can be used in courts.[206]

In resolving high-volume consumer finance disputes, a notable effort is the inter-branch “General-to-General” (Zong Dui Zong, meaning direct cooperation between central agencies) online financial dispute resolution mechanism.[207] The SPC first established an online mediation platform and connected this platform with a network of agencies including the People’s Bank of China, the Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the Securities Regulatory Commission, among others.[208] The SPC, together with these agencies, formed a China Financial Consumer Dispute Mediation network aimed at resolving disputes upfront outside the courtroom.[209] Under this program, the People’s Bank of China has helped gather 510 mediation organizations and over 5,600 specialized mediators under this network.[210] Together, they have cooperated in 22,100 disputes through online mediation.[211]

A parallel initiative, the Banking and Insurance Online Mediation System, was co-developed by the SPC and the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission in 2021. The program harnesses digitization to let “data . . . do more work and the public . . . do less.”[212] By 2022, the platform had onboarded over 500 financial mediation organizations and over 5,600 mediators.[213] Courts have been able to delegate more than 30,000 pre-litigation mediation cases using this program.[214] Empirical studies have shown that the mechanism has the potential to ease the burden on courts and ensuring judicial resources are allocated efficiently.[215]

Adding to these efforts, many regions have put into use the “Litigation Risk Assessment” (Susong Fengxian Pinggu) software to inform litigants of the “risks” of bringing lawsuits.[216] This system requires would-be plaintiffs to complete a digital survey before filing a lawsuit. The survey analyzes factors such as the plaintiff’s likelihood of success, estimated costs, and anticipated duration of the case. Today, litigation risk assessment has been integrated into a nationwide service of People’s Courts Online Services (Renmin Fayuan Zaixian Fuwu).[217] This tool discourages unnecessary filings and empowers unrepresented individuals to make informed decisions.

Within courtrooms, Chinese reforms focus on balancing efficiency and fairness through simplified procedures and digital tools. One key initiative is the use of artificial intelligence (“AI”) to assist in adjudication. For instance, in the Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court, judges first reach an initial decision in a case and then use a large language model (“LLM”) to generate draft legal reasoning supporting that decision, which judges subsequently review and revise before issuing the final judgment.[218] Similarly, the Changchun Intermediate People’s Court, in collaboration with iFlytek’s legal AI team, developed the “Private Lending Intelligent Judicial Calculator (Minjian Jiedai Zhineng Sifa Jisuanqi)” to standardize the calculation of principal and interest, an issue that accounted for nearly half of appellate reversals.[219] Judges input basic loan and repayment information into the system, which then uses an algorithm to automatically process repayment sequences, loan periods, interest rates, overdue penalties, and principal deductions in accordance with legal regulations. The tool generates detailed, accurate results instantly, including a breakdown of the calculation process, enabling judges to verify outputs easily. It is reported that this AI-powered system can handle 10,000 first-instance cases annually in the Changchun region and helps reduce errors, boost efficiency, and enhance the quality of judicial decisions.[220] Similar automotive adjudicative tools are also used in Shanghai, Zhejiang, among other regions.

Beyond individual cases, centralized case management systems enable courts to identify patterns of fraudulent behavior. For instance, the “Unlicensed moneylenders directory” has been established by courts in Zhejiang, among other provinces, to identify entities engaging in predatory lending by tracking the frequency of lawsuits they file.[221] In Zhejiang, the database was established through joint efforts between the judiciary and six other government departments, including financial regulators and the police department. The system not only aids in adjudication but also constitutes a data-sharing platform between courts and other departments to promote financial consumer protection.[222]

The Beijing financial court developed another interesting application of inter-branch information exchange called “smoking index.”[223] The index aggregates diverse datasets, from business records to banking statements, to monitor high-risk financial activities.[224] When a flagged corporation enters litigation, judges receive automatic alerts, enabling them to scrutinize potential misconduct more effectively.[225] Courts also feed docket information into the system, which uses machine-learning algorithms that could aid in detecting fraudulent behaviors such as shadow banking and predatory lending.[226] This system enables judges within the Beijing court system to have access to litigants movements and thus carry on more organized court proceedings. [227]

The lifecycle navigation of A2J extends beyond adjudication. There are mainly two goals in this stage. One is to ensure effective enforcement of judgments, and the other is to prevent the recurrence of similar disputes. First, to ensure enforcement, the SPC established a national asset investigation database that aggregates information from sixteen government agencies—including the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Civil Affairs, the Ministry of Natural Resources, the Ministry of Transport, the People’s Bank of China, and the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission—as well as from more than 3,900 financial institutions.[228] This system allows courts to access over twenty-five types of asset information related to judgment debtors, including real estate holdings, bank deposits, securities, vehicles, vessels, online assets, and financial investments.[229] This ensures that courts more effectively identify debtor resources and prevent asset concealment.

Another example that reflects the lifecycle approach to navigate A2J is the “Online Enforceable Notarization System (zaixian fuqiang gongzheng).”[230] Designed particularly for debt collection cases, the system connects financial institutions, notary offices, and courts to streamline dispute resolution and prevent disputes from happening upfront.[231] Specifically, financial institutions can initiate notarization procedures for loans and credit agreements directly through the platform, which are then authenticated by online notary offices.[232] In cases of default, the notarized agreements—recognized as legally binding documents—can be swiftly transferred to courts for enforcement without requiring additional validation processes.[233] The whole data storage is achieved by blockchain technology, which ensures that records of transactions, agreements, and enforcement are immutable and verifiable. The system also integrates real-time analytics to identify patterns of default and potential financial risks. Research shows that borrowers, particularly those from rural or underserved areas, benefit from simplified online procedures that reduce the need to physically visit notary offices or courts.[234]

The second goal is to prevent the recurrence of similar disputes. Courts in China continue to actively work with other state departments to prevent the recurrence of similar disputes. A key mechanism is called “judicial suggestions,” which allows courts to formally recommend policy or legislative changes based on docket analysis.[235] Judicial suggestions regarding insights from debt collection dockets are often shared with other government agencies to promote access to justice. The SPC, for example, has explicitly stated that “[w]here it is found trading platforms . . . are involved with usury activities under the pretext of ‘innovation,’ the people’s court shall, in a timely manner, resolutely curb such violations by effective means such as issuing judicial recommendation letters.”[236]

Beyond the central level, local courts also actively use judicial suggestions to enhance their roles as social problem solvers. It was reported that the Huaihua Intermediate Court, an appellate court in Hunan province, analyzed over 300 financial lending disputes in 2024 and identified systemic issues to share with financial regulators.[237] These issues include debtors evading obligations through false identities, improper debt transfers that may lead to privacy breaches, and excessive interest rates that exceed legal limits. In response, the local financial regulatory office conducted a comprehensive review of lending practices across local financial institutions, launched targeted investigations, and introduced new compliance measures according to the judicial suggestions.[238] Similarly, the Nanshan Court in Shenzhen issued judicial suggestions after identifying recurring problems in financial lending disputes, including inaccurate borrower information, inadequate evidence preservation by financial institutions, and unethical lending practices.[239] The court then worked with the local financial industry association to propose upfront reforms at the loan-issuing state, such as stricter borrower verification processes, enhanced digital evidence management, and industry-wide adoption of standardized contract templates.[240] These suggestions resulted in policy adjustments and the establishment of a financial dispute resolution platform to prevent similar disputes.[241]

While China’s lifecycle approach to A2J reforms demonstrates how systemic strategies can be leveraged to manage judicial workload and increase efficiency, what are the potential trade-offs? First, judicial autonomy faces new challenges under digitized oversight. Technology, while improving efficiency, is also used to monitor and evaluate judicial behavior in Chinese courts.[242] SPC reported that they can now monitor more than thirty performance metrics for individual courts, from average adjudication time to the proportion of cases resulting in litigant complaints.[243] As some commentators have noted, judicial digitalization in China blurs the boundary between adjudication and court administration, threating the independence and autonomy of judges.[244]

Second, individual rights, especially privacy, might be at risk in the push for efficiency and cross-department data sharing. The extensive sharing of sensitive personal and business information across public institutions risks data use beyond the immediate needs of adjudication. Furthermore, the increasing reliance on mediation and risk assessment tools may compromise traditional due process values by reducing opportunities for full hearings.[245]

Third, the strong push for court digitization also risks exacerbating regional disparities through the uneven development and deployment of digital infrastructure. Empirical studies have shown that while some jurisdictions have achieved deep integration of digital tools into judicial workflows, others struggle with superficial or fragmented implementation.[246]

Together, China’s lifecycle approach to A2J illustrates how systemic reforms can be leveraged to address A2J challenges in an increasingly litigious society. To be sure, these reforms, while ambitious and impactful, raise important questions about judicial autonomy, due process, regional disparities, among broader concerns over centralized governance. Nevertheless, they offer an alternative model for understanding the prevention-based, inter-branch, data-driven systemic reforms in a digital age.

As discussed in previous Parts, ultimately, the American resistance to digital systemic reforms on A2J is not just a policy issue but a deeply embedded structural and cultural challenge. The reliance on private litigation to solve social problems and the lawyer-driven dispute resolution are deeply intertwined with rule of law values, notably the separation of powers and due process. However, this rigid understanding of the rule of law, combined with the entrenched interests of the legal profession, creates barriers to adopting more effective digital systemic reforms that have been effectively implemented in other jurisdictions.

Could prevention-based, data-driven, and inter-branch systemic reforms be compatible with rule of law values that safeguard against authoritarianism? While a full account of the rule of law is beyond the scope of this article, this Part contends that the concept of rule of law should be understood not as a static ideal but as a spectrum. Both judicial reliance and adversarialism are products of specific historical and societal contexts in America, but they are not synonymous with either separation of powers or due process, which exist along a broader spectrum of rule of law values.

To start with, the rule of law does not inherently require reliance on courts as the sole venue for addressing social issues. Under certain conditions, granting policymakers the flexibility to choose between general rulemaking and case-specific adjudication can better promote formal and procedural rule-of-law principles than rigid adherence to an extreme separation of powers.[247]

Historically, the separation of powers has never been a static principle with universally agreed boundaries. In Ancient Greece, the tripartite division of government functions was still nascent. Aristotle himself argued that “[w]hether these functions . . . belong to separate groups, or to a single group, is a matter which makes no difference to the argument.”[248] By the Enlightenment, the notion of an independent judiciary began to take shape, yet still Locke and Montesquieu held very different opinions on whether the judiciary should constitute a unique branch that is equal to other branches.[249] In Locke’s view, the judiciary was not an autonomous function of the House of Lords,[250] while for Montesquieu, there is an independent branch of the judiciary.[251] Then, the founding fathers of the United States made hard efforts to keep different functions of powers apart as a fundamental precaution against abuse. But even among them, the separation of powers was not an absolute idea. James Madison, for instance, had a central insight that we should not conceive of the legislative, executive, and judicial power as “wholly unconnected.”[252]

The rise of the regulatory state in the 20th century marked another shift.[253] The emergence of massive corporations posed severe challenges to market regulation as they leveraged their dominance to undermine individual rights.[254] While abuses of public power remain a serious concern, private abuses of legal entitlements can equally threaten the rule of law, which necessitated a more robust supervisory architecture that transcends strict separation of powers. In response, administrative agencies were tasked with overseeing these entities through a combination of rulemaking, enforcement, and adjudication.[255] This fusion of powers was guided by the rationale that “[t]he form of the agency must follow the form of the concentrated entities it regulates.”[256]

A body of classic and recent public law scholarship has further emphasized the cooperative dimensions of separation of powers, advocating for coordinated institutional efforts to achieve good governance. For instance, the “collaborative constitution” theory contends that the separation of powers is underpinned by a deeper value of coordinated institutional effort between branches of government in the service of good government, or “joint enterprise of governing” with the requirement of “inter-institutional comity.”[257] The “constitutional dialogue” theory emphasizes that certain interactions between courts and legislatures, including but not limited to judicial review, can help democratically protect rights.[258] The “political process theory” sees that courts generally shoulder a moral responsibility to reinforce the representation of elected branches and to police the democratic flaw by legislature.[259]

To be sure, strengthening the coordination between government branches does not entail sacrificing judicial independence. As Professor Susskind has emphasized, we should “draw a very firm distinction between . . . the primary and secondary functions of online courts.”[260] This distinction underscores the need to functionally separate judicial adjudication from judicial data management. While court digitization should be promoted to enhance access to justice, activities such as data collection, analysis, and administrative innovation must remain structurally insulated from the judiciary’s core adjudicative functions. The respective responsibilities of judges and court administrators must be carefully delineated to preserve the independence and integrity of judicial decision-making.[261]

In sum, the separation of powers should not be understood as a rigid, clearly defined principle but as a spectrum. On one end lies the purest form of functional separation, where powers remain entirely distinct, while the other end features a more coordinated approach, where different powerholders collaborate to fulfill overlapping functions. The position of any constitutional design on this spectrum depends on cultural contexts and the evolving needs of society. Recognizing this flexibility allows for more effective address of modern challenges, such as A2J in the digital age.

Parallel to the evolving notion of separation of powers is the transformation of due process. We need a more flexible understanding of the rule of law, which would expand our conception of due process beyond lawyer-driven adversary procedures. Due process, broadly understood as the fairness and transparency of legal processes, is an essential component of the rule of law. It ensures that individuals are treated equitably and that decisions are made through established and predictable methods. However, it is not a static concept; its meaning and implementation vary across legal traditions and societal contexts. Scholars have long observed that procedural design reflects the political, cultural, and psychological commitments of a given jurisdiction, with adversarial and inquisitorial models embodying competing visions of justice.[262]

Historically, adversarial procedure has been linked to “liberty-promoting, possibly democratic governments,” while inquisitorial procedure was often associated with “monarchical, possibly authoritarian regimes.”[263] Put differently, the adversarial model often serve as a safeguard against potential government overreach.[264] In contrast, the inquisitorial model rest on the idea that state actors can provide expert, impartial oversight to correct for structural inequalities and private power imbalances.[265]

However, this traditional dichotomy no longer holds firmly. Even within the United States, adversarialism has never been the exclusive procedural mode. As Professor Kessler writes about the history of American adversarialism, equity courts, inspired by the English tradition, offered more flexible, “judge-empowering, quasi-inquisitorial” approaches to dispute resolution, particularly in areas like trusts, family law, and specific performance.[266] Similarly, conciliation courts, “transplanted from continental Europe[,]” emphasized non-adversarial methods to resolve disputes efficiently and equitably.[267] These traditions illustrate that adversarialism, while influential, is not synonymous with procedural justice or the rule of law.[268] Similarly, the civil justice reforms introduced in England during the mid-1990s through Lord Woolf’s Access to Justice reports are often seen as having softened the adversarial model by promoting greater use of alternative dispute resolution and encouraging judges to take a more proactive role in managing cases.[269]