Tax Administration and Racial Justice: The Illegal Denial of Tax-Based Pandemic Relief to the Nation’s Incarcerated Population

By

By

Leslie Book*

In the midst of a devastating pandemic that would sicken millions, kill hundreds of thousands, and cause widespread financial distress, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, a broad-based emergency pandemic relief measure.[1] A key part of that relief, the immediate delivery of up to $1,200 for adults and $500 for dependent children, was delegated to the Department of the Treasury and the organization within the Treasury responsible for administering the internal revenue laws, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).[2] The stimulus was ostensibly structured as a refundable credit to be claimed on a 2020 tax return in 2021[3] but with a twist. The statute authorized the IRS to pay the stimulus in advance, even to those who did not have a tax return filing obligation, and to do so as “rapidly as possible.”[4]

Congress essentially asked the IRS to step in and provide most households with financial assistance in response to the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. The CARES Act required the IRS to determine eligibility and payment amount by using information it had on file from individual tax returns filed in either 2018 or 2019.[5] For federal beneficiaries who did not file tax returns in either of those years, the statute authorized the IRS to use information it had on file from the Social Security Administration.[6] Within weeks, the IRS also established an online portal that would allow it to pay individuals with little or no connection to the tax system.[7]

Although there were some problems, the IRS did remarkably well, especially in comparison to a similar payment program enacted in 2008. Within six months, it had delivered approximately 160 million economic impact payments (EIPs) totaling over $270 billion.[8] There were some exceptional problems, however, and this is the story of one of those problems.[9] It involves the IRS’s unexplained change in position regarding the eligibility of over 1.3 million federal, state, and local prisoners to receive EIPs.[10] At first, prisoners—just like millions of other Americans suffering from the effects of the pandemic—received the money they were entitled to receive under the CARES Act.[11] That soon changed. A report by the Treasury Inspector General, which provided a mid-year snapshot of the IRS’s activities, detailed a puzzling series of events.[12] The Inspector General informed the IRS that, by early April, it had issued nearly 85,000 EIPs to incarcerated individuals, totaling approximately $100 million.[13] The IRS reported back to the Inspector General that the CARES Act did not prohibit prisoners from receiving EIPs.[14] The Inspector General then stated that the “IRS subsequently changed its position, noting that individuals who are prisoners are not entitled to the EIP.”[15]

In the same report, the Inspector General noted that the IRS took swift action to recover over 955,000 EIPs it had previously sent to prisoners and to ensure that, as it finished its mandate of paying emergency cash to Americans, it did not send EIPs to incarcerated individuals who did not receive EIPs before the IRS reversal.[16] By May 6, 2020, the IRS categorically and publicly stated, though without legal explanation, that prisoners were not entitled to receive EIPs.[17] The agency communicated its position through an online post in the form of a frequently asked question (FAQ), also stating that prisoners who had previously received an EIP should return either a voided check or the funds they received in error.[18]

On August 1, 2020, Colin Scholl and Lisa Strawn, two impacted individuals, filed a lawsuit seeking class action status on behalf of the nation’s prison population, challenging the IRS’s position as unlawful under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).[19] Scholl previously filed a 2019 tax return that should have generated the automatic payment.[20] Strawn was unable to file a claim through the separate non-filer portal despite the CARES Act’s mandate that the IRS pay funds as rapidly as possible.[21]

In under three months, the prisoners won a complete victory. The district court in Scholl v. Mnuchin issued an injunction ordering the IRS to withdraw its “arbitrary and capricious” position and ensure eligible prisoners receive the same payments generally delivered to others.[22]

What lessons can be learned from the IRS’s actions with respect to the prison population? There are many potential ways to approach the issues presented in Scholl. For example, the case is a window into the intersection of administrative law—the APA, in particular—and tax administration. It also provides an opportunity to examine procedural defenses, like standing and sovereign immunity, which are part of an impressive gauntlet the government can use to defer court review of IRS actions until a traditional enforcement proceeding occurs, often years from when the actions have an immediate impact.[23]

This Article approaches the IRS’s actions from a different perspective: how the IRS’s administration of the tax law can reinforce race-based power disparities and perpetuate racial injustice. By first announcing that it would no longer issue EIPs to prisoners, then working with prison officials to recover lawful payments already made, and then failing to facilitate a remedy allowing for prompt payment even after a court found its actions improper, the IRS harmed not only the incarcerated population but also their families who regularly struggle with the absence of a person who may be the primary source of household support.[24] This had an outsized impact on African-Americans and Hispanics, who comprise a disproportionate share of the population in state and federal prisons and the population of those infected during the pandemic.[25]

Following the videotaped murder of George Floyd, the IRS’s actions came at a time of social unrest. That killing set widespread action and reflection in motion, even among the majority white population that, at times, has been at best apathetic to the problems that communities of color face in society at large and in the criminal justice system in particular.[26] It sparked a conversation as to how individuals can transition from being non-racist to anti-racist. This Article contributes to that discussion by revealing how the mundane world of tax administration[27] can exacerbate racial disparities and inequity.

How does this contribution fit into the scholarly discussion about the IRS and its increasingly important role as a benefits administrator?[28] I and others, like former National Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson, have previously argued that, to successfully fulfill its role as a key player in our nation’s safety net, the IRS must directly acknowledge its role as a benefits administrator and not just its role as a tax collector.[29] The events of this past year have led me to reconsider that advice. It is necessary but insufficient that the IRS acknowledge its expanded role. The IRS must affirmatively recognize the role that administering benefit programs can play in perpetuating our nation’s racial inequities. By directly considering the racial composition of its actions (and, at times, inactions), the IRS can position itself to help our society overcome the racial injustice that has existed since the creation of the United States. It can be an agent for positive change. Or, as in the actions it took with respect to prisoners and eligibility for pandemic relief, it can be an agent for harm.

This Article comes at a time of increasing interest in the relationship between federal tax policy and race in the legal academy.[30] This contribution highlights a category within that field: namely, the relationship between tax administration and race. Tax administration focuses on the manner in which the IRS administers the tax law found within the Internal Revenue Code. Tax administration consists of the IRS’s guidance as well as its enforcement priorities, including how the IRS ensures taxpayers meet their tax return filing obligations, who the IRS decides to audit, and how the IRS takes enforced collection action against delinquent taxpayers. While there has been some interest in the racial impact of the IRS’s audits of low- and middle-income taxpayers claiming refundable credits,[31] this field is relatively underexplored. This Article attempts to take a racial perspective on tax administration, especially as it relates to the IRS’s increasingly important role in administering social welfare programs, often in the form of refundable credits.[32]

Before proceeding, I offer some preliminary observations. First, as a scholar who has not previously engaged with race directly and as one who is a white male, I address the topic with some trepidation. While I have spent the better part of my professional life working with (and, at times, for) the IRS and writing about tax administration, prior to the unrest in the spring and summer of 2020, I had not thought deeply about the relationship between racial justice and tax administration. Second, in offering my observations, I am not making the claim that any individual or individuals within the IRS were explicitly racist in determining that prisoners were ineligible to receive EIPs.[33] Instead, as others have powerfully explored, racist policies can occur even when no one individual consciously discriminates.[34] Third and finally, much work is needed to evaluate the relationship between race and tax administration. To that end, there is a deep need for data that would allow policy makers to explore differing policies and practices that could potentially allow tax administration to be a tool for an anti-racist agenda.[35]

This Article proceeds as follows: Part II reviews the legal action brought on behalf of state and federal inmates challenging the IRS’s policies toward the incarcerated, highlighting both the government’s defense to its actions and, ultimately, the judicial system’s direct rebuke of the government’s procedural and substantive defenses.[36] Part III considers the context of the IRS’s actions, looking at the racial disparities among millions of incarcerated individuals as well as the ways in which individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Part IV explores the concept of racialized burdens, evaluating recent scholarship’s exploration of the relationship between frictions that prevent individuals from receiving benefits or services from the state and the ways in which those burdens can have an outsized impact on racial minorities.[37] The concept of racialized burdens demonstrates how tax administration can, at times, normalize and reinforce patterns of racial inequality even in the absence of rules that overtly identify people of color for adverse treatment. Additionally, Part IV offers preliminary observations as to how the IRS’s actions—with respect to EIPs and the incarcerated population—can offer lessons to minimize the risk of harm to racial minorities and potentially act as an agent to combat our nation’s racial injustice.

Less than three months after the IRS claimed prisoners were ineligible to receive EIPs, advocates from Leiff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein and the Equal Justice Initiative filed a class action lawsuit against the IRS, the Treasury Department, and the United States in the Northern District of California. In addition to the named plaintiffs, Colin Scholl and Lisa Strawn, the proposed class included individuals who “have been incarcerated in the United States at any time from March 27, 2020 to the present” and who were eligible for EIPs under the CARES Act and § 6428 of the Internal Revenue Code.[38]

The plaintiffs alleged that, in withholding EIPs from individuals who would be eligible but for their incarcerated status, the IRS’s actions violated § 6428, as amended by the CARES Act.[39] In particular, the plaintiffs highlighted the IRS’s work with prison officials to claw back previous payments by categorically denying payments to prisoners.[40] As the plaintiffs alleged, § 6428 defined payment eligibility broadly, with no status-based limits other than excluding individuals who were nonresident foreign nationals and who could be claimed as dependents by other taxpayers.[41] The plaintiffs sought equitable relief through the APA, which generally provides a cause of action for challenging final agency actions that are contrary to law or are otherwise arbitrary and capricious because the agency failed to justify its decision with a contemporaneous explanation.[42]

Throughout the complaint, the plaintiffs emphasized that the IRS had yet to provide any explanation for withholding payments from otherwise eligible individuals.[43] Notably, an IRS spokesperson is quoted as stating, “I can’t give you the legal basis [for withholding payments]. All I can tell you is the language the Treasury and ourselves have been using.”[44]

The district court entered a preliminary injunction against the defendants on September 24, 2020.[45] The order enjoined the defendants from “withholding benefits pursuant to the CARES Act . . . . on the sole basis of [an individual’s] incarcerated status.”[46] Soon after, the defendants filed an appeal as well as a motion for stay pending appeal.[47] The plaintiffs subsequently filed a motion for summary judgment on their APA claims, the success of which would depend on one of those claims: whether the IRS’s actions were “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law.”[48]

Noting that “the focal point for judicial review [in cases applying the plaintiffs’ APA claims] should be the administrative record already in existence,” the court addressed, as a threshold issue, whether summary judgment was appropriate.[49] The court concluded summary judgment was proper even though the IRS failed to provide a certified administrative record, the plaintiffs submitted sufficient information from the IRS, the government itself provided sworn declarations by the named plaintiffs and IRS executives, and the government offered no challenges to any documents the plaintiffs provided.[50]

When it addressed the merits of the APA claims, the court first analyzed whether the IRS’s actions were contrary to 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A) and in excess of the agency’s statutory authority. In finding the IRS’s actions were inconsistent with § 6428, the court considered both the statute’s language and its structure. Relying on persuasive authority from the Second Circuit, the court concluded § 6428 requires the defendants to issue advance refunds as rapidly as possible.[51] Further, the court denied the defendants’ assertions that the CARES Act merely provided a tax credit (as opposed to a $1,200 cash payment), noting that the Act “provides an explicit mechanism for immediate and mandatory distribution of the refundable credit.”[52]

The court concluded the statute did not leave eligibility open-ended, remarking that, in prior versions of § 6428, Congress explicitly excluded incarcerated individuals but the CARES Act did not have the same exclusion.[53] Noting its previous finding that the statute was clear and that the defendants “advance[d] no arguments to the contrary[,]” the court affirmed its holding and determined the government’s position was “not in accordance with the law” under the APA.[54]

The court also found the IRS’s position was contrary to the APA because its actions were arbitrary and capricious.[55] The court noted that an arbitrary and capricious analysis focuses on the reasonableness of the agency’s decision-making process.[56] The defendants failed to provide an adequate reason for their decision to exclude incarcerated individuals from eligibility under the CARES Act. Although the defendants cited concerns about fraudulent tax returns and other frivolous tax activity involving incarcerated individuals, the court dismissed these concerns as “impermissible post hoc rationalization[s]” because they were not offered contemporaneously with the IRS’s decision.[57]

Although the plaintiffs in Scholl were victorious, implementing the court’s decision and, most importantly, getting the cash that most Americans received with little or no effort was, and continues to be, a challenge.[58] The court’s October injunction enjoined the government from withholding payments due to prisoner status, ordered payment to eligible prisoners, and mandated that the government take “all necessary steps” to effectuate a policy that would not prevent prisoner eligibility for EIPs.

As a threshold matter, there was a very short period of time during which prisoners could provide information to the IRS following the court’s permanent injunction on October 14, 2020. This is because the CARES Act required the IRS to issue EIPs as rapidly as possible but imposed a December 31, 2020 deadline to issue the money.[59] For individuals the IRS previously identified as incarcerated, the Scholl victory generated actions that the IRS took on its own. For example, the IRS reconsidered the eligibility of 385,995 individuals who were previously identified as incarcerated; made payments totaling $465,233,776; and withdrew its prior request for approximately 950,000 prisoners to return their EIPs—protecting approximately $1.14 billion in benefits.[60]

The real problem was that the IRS did not have sufficient information for hundreds of thousands of prisoners before the year-end deadline. The IRS, with the court’s approval, imposed a November 4 deadline for receiving mailed tax returns and a November 21 deadline for entering information on the non-filer portal—deadlines that were applicable to other eligible individuals. Following the decision, incarcerated individuals throughout the country were not notified within the time period set forth in the injunction and others were not notified at all, creating a key challenge for prisoners who were not set to automatically receive their EIPs.[61]

It was also complicated for the IRS to gather important information even from prisoners who were informed of the court’s decision. The IRS created the non-filer portal for individuals who did not file a tax return in 2019 to enter identification and payment information.[62] However, because incarcerated individuals could not access the portal and the IRS did not allow family members to use the portal on their behalf, they were left with no way to inform the IRS of their eligibility.[63]

In response to the inaccessibility of the non-filer portal, the IRS created a “simplified” form on which eligible individuals could report their information.[64] This form, however, came with its own problems. The form itself was confusing.[65] It resembled a traditional Form 1040, but it directed filers to only address highlighted sections.[66] The plaintiffs’ counsel noted it was difficult for prisoners to complete and called for the IRS to simplify the form further.[67]

An additional problem for those able to navigate the barriers was that the IRS requested thousands of prisoners to supply additional identity verification before it would issue EIPs.[68] The IRS sent a letter asking prisoners to call a hotline within thirty days of receiving the letter. That request created significant problems, as plaintiffs’ counsel informed the court in a status report filed on December 8, 2020:

Class counsel have received multiple urgent requests for help from Class Members who have received letters from the IRS asking them to call an IRS verification hotline within thirty days of the letter. Unfortunately, even when Class Members have tried (often over and over for days or weeks) they have been unable to complete their application and now fear it will be rejected through no fault of their own. In particular, the hotline has been so understaffed that it will either not permit callers to remain on hold because the queue of callers is too long, or it will permit callers to wait in a queue for the next available agent, but then remain on hold for so long (e.g., 20 minutes o[r] longer) that those who are incarcerated are forced to terminate the phone call for reaching the allotted call time or phone privileges of their correctional institution. Class counsel have contacted IRS repeatedly about this, including at the request of various concerned correctional institutions, but IRS counsel has not responded.[69]

In sum, while the Scholl litigation resulted in a resounding victory for incarcerated individuals, there were multiple problems that prevented them from receiving the EIPs they were legally entitled to. Challenges in adequately notifying prisoners,[70] backlogs in the IRS’s information processing among those who overcame initial obstacles, and harmful actions by prison officials themselves were all formidable barriers that blunted the effect of Scholl’s success. These difficulties prevented hundreds of thousands within the prison population from receiving the cash that Congress intended to deliver “as rapidly as possible”—forcing those who did not receive EIPs by December 31 to claim the credit on their 2020 tax return. What was possible for many outside the prison system was simply impossible for those inside.

The Scholl court concluded the IRS acted ultra vires when it classified prisoners as ineligible for EIPs solely upon their incarcerated status.[71] As the court explained in its order granting summary judgment for the plaintiffs, the IRS failed to offer any contemporaneous evidence that would justify or explain its decision.[72] This Part provides additional context to the harm that the IRS’s position, if gone unchecked, would have inflicted on incarcerated individuals and their families. In examining the impact of the IRS’s actions, this Part explores the financial and racial context of the IRS’s decision and the ways in which the racial disproportionality among incarcerated individuals mirrors the racial disproportionality among those most harmed by COVID-19.

Incarcerated individuals, as with other members of society, have pressing financial and personal needs—exacerbated by the pandemic—that place them in a position of needing economic relief. Hundreds of thousands are released from custody annually,[73] generally struggling to gain a stable economic footing due to various factors, such as hiring discrimination and wage suppression.[74] Because the economic effects of the pandemic are not equally distributed across employment sectors, those recently released from custody face even greater pressures than usual, thus highlighting the need for the EIPs that the IRS withheld.[75]

Even among those who were not set for release in 2020, the nation’s prisoners and their families struggle financially, with incarceration at times caused by an individual’s inability to pay fines or fees. Generally, once incarcerated, inmates are responsible for purchasing hygiene products, extra food, and access to communication.[76] Despite the high costs of these items, many states claim a certain percentage of an inmate’s already low wages or income to cover any owed restitution or other costs.[77] Notably, inmate wages in the United States, often less than $1 per hour, are significantly lower than the federal minimum wage.[78] Each of these factors causes significant financial hardship for inmates and their families.[79] As incarceration is concentrated in economically disadvantaged communities,[80] the IRS’s denial of cash to those communities has an outsized impact on individuals who are already struggling in the first instance.

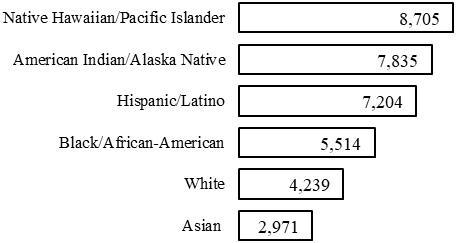

This context must also include the racial disproportionality among the U.S. prison system, which also happens to track the racial disproportionality of those most harmed by COVID-19. In the United States, approximately 2.3 million inmates are incarcerated in federal, state, and local jails and prisons.[81] Despite representing only 32% of the American population, African-Americans and Hispanics comprise 56% of the incarcerated population.[82] Put differently, “African-American adults are 5.9 times as likely to be incarcerated than whites and Hispanics are 3.1 times as likely.”[83] The following table from the Prison Policy Institute presents a clear visual of these disparities.[84]

In addition to disparities in the U.S. prison system, there are striking racial disparities associated with COVID-19, which has disproportionately harmed people of color.[85] An analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Epic Health Research Network found COVID-19 hospitalization and death rates per 10,000 at 24.6 and 5.6 for Black patients, 30.4 and 5.6 for Hispanic patients, and 15.9 and 4.3 for Asian patients. In contrast, hospitalization and death rates were much lower for white patients, at 7.4 and 2.3.[86] While the reasons for these disparities are not fully known, a recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association encapsulates some likely reasons:

In the US, racial and ethnic minority status is inextricably associated with lower socioeconomic status. Black, Hispanic, and American Indian persons in the US are more likely to live in crowded conditions, in multigenerational households, and have jobs that cannot be performed remotely, such as transit workers, grocery store clerks, nursing aides, construction workers, and household workers. These groups are more likely to travel on public transportation due to lack of having their own vehicle. Even for persons who can shelter at home, many persons with low incomes live with an essential worker and have a higher likelihood of exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.[87]

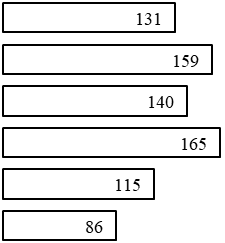

The COVID Tracking Project and the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research has been tracking race and ethnicity data on the effect of the pandemic across the United States. The following table presents a clear image of one aspect of the disease’s racial disparities, looking at infections and deaths per 100,000 across the country as of February 14, 2021.[88]

Figure 2. COVID-19 Demographics

Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders were most likely to have contracted COVID-19.

Black/African-Americans were most likely to have died from COVID-19.

Cases per 100,000 people

Deaths per 100,000 people

The above discussion illustrates the IRS’s efforts to deliver emergency relief and the adverse impact of its policies on the prison population, especially on people of color who comprise a disproportionate percentage of that group. Before and after the Scholl litigation, the IRS’s actions harmed many but had a greater impact on Brown and Black individuals who were incarcerated and suffering from COVID-19 at higher rates than other Americans. This Part provides a broader context for the IRS’s actions, leaning on insights from sociology and public administration scholars Victor Ray, Pamela Herd, and Don Moynihan. Their work highlights how agencies can impose administrative burdens in ways that normalize and reinforce patterns of racial inequality even in the absence of rules that overtly identify or penalize people of color.[89] After providing context, this Part becomes prescriptive by suggesting ways the IRS can combat the forces of inequality rather than help perpetuate them.

Congress’s decision for the IRS to deliver cash payments that seek to ameliorate the effects of the pandemic highlights the IRS’s role as a benefits administrator.[90] That role differs from the IRS’s role as a revenue collector, where the IRS has traditionally taken an approach rooted in enforcing rather than ensuring access to services or benefits.[91] The use of the tax system to provide cash needed during this health and economic emergency follows the legislative trend of using tax law for an increasing array of social welfare and regulatory policies, such as health care, retirement security, and low-wage income supplements, that have little or no relationship to the IRS’s long, primary mission of collecting revenue.[92] Accepting the IRS’s role as a gatekeeper of benefits allows the IRS, policy makers, and scholars to consider insights from other disciplines, such as public administration and sociology, as well as legal theories that are less associated with the tax system, such as procedural justice and procedural due process.[93] The concept of racialized burdens was introduced in Racialized Burdens: Applying Racialized Organization Theory to the Administrative State by Professors Ray, Herd, and Moynihan.[94] The authors provided a perspective outside of the legal academy that reveals a deep racial context for the actions described in this Article.

To understand racialized burdens, one must first define the concept of administrative burdens more broadly. Administrative burdens are frictions or costs individuals experience when interacting with government agencies in an attempt to receive public services.[95] In prior work, Herd and Moynihan—looking at diverse areas, including access to voting, health care, and Social Security benefits—categorized frictions into three main categories: learning costs, compliance costs, and psychological costs.[96] Learning costs relate to the costs associated with discovering eligibility for, and application to, a particular program.[97] Compliance costs include the costs of filling out forms, waiting in line, or responding to bureaucratic requests to prove eligibility.[98] Psychological costs include the stress, anxiety, and stigma associated with applying, receiving, or proving eligibility.[99]

In Racialized Burdens, Ray, Herd, and Moynihan advanced the concept of administrative burdens by identifying three key points essential to understanding the relationship between those burdens and racial inequality.[100] First, what may appear to be a small burden on the surface may in fact have large effects on one’s access to rights, benefits, or services.[101] Second, the effects of burdens are not equally distributed—groups with less power and resources, such as racial minorities, suffer from the effects more than others.[102] Third, burdens may arise from deliberate choices, with policy makers at times imposing burdens to frustrate goals in a manner that is difficult to detect and that would otherwise be impermissible to achieve legislatively or be constrained by law or norms.[103]

Racial organization theory, a subset of organization theory,[104] emphasizes that the state and its organizations are not part of a race-neutral bureaucracy. Failing to consider race when examining governing organizations allows for a failed exploration of racial inequality patterns. Ray, Herd, and Moynihan aptly described racial organization theory’s relationship to broader organization theory principles, stating:

Racialized organization theory argues that race neutrality central to much organizational theory may be possible in the abstract, but in practice, entrenched ideas about racial superiority and inferiority mean that state and private organizations typically distribute resources along racial lines in ways that advantage dominant groups.[105]

Putting the concept of administrative burdens together with racial organization theory directed Ray, Herd, and Moynihan to focus on the ways in which burdens interact with race, leading to what they referred to as “racialized burdens”:

Adding a racialized organizational perspective to administrative burdens shows that burdens neatly carry out the “how” in the production of racial inequality while concealing, or providing an alibi for, the “why.” Administrative burden provides a lower profile and colorblind gloss for politicians that might be sanctioned for openly disenfranchising Black voters or denying welfare recipients their benefits. By complicating seemingly neutral policy preferences, politicians and administrators can effectively leverage a tool to maintain white domination.[106]

Using this framework, the authors discussed “how administrative burdens act as the handmaidens of racialized organizations” and then illustrated the concepts in the context of immigration, voting rights, and the social welfare system.[107] They emphasized how burdens can enhance or diminish the agency of racial groups by imposing requirements that diminish resources (like for example, time) and how burdens may be decoupled from formal rules to ensure that organizational actions are racialized.[108] By hiding behind facially neutral rules, burdens that impact people of color benefit from a surface neutrality and allow agency employees, who may be anti-racist personally, to separate themselves from what may, in fact, be promoting an institutionalized racist policy.[109]

The application of this framework to traditional welfare programs provides the closest analogy to Congress’s use of the tax system to provide the means-tested pandemic relief discussed in this Article. Ray, Herd, and Moynihan noted that traditional means-tested social welfare policies, like Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), disproportionately shift burdens to beneficiaries.[110] In contrast, more universal social insurance policies, like Social Security or the income exclusion for employer-based health insurance, tend to place the burdens on the government or third-party employers.[111] For example, traditional welfare recipients must prove their entitlement to benefits by submitting complicated forms and verifying eligibility in person. This is contrasted with Social Security, which presumptively determines eligibility and benefit levels based on information reporting, and the exclusion from gross income for employer-paid health premiums, which is tied to employers who must comply with detailed requirements to establish and maintain employee plans that allow employees to qualify for tax benefits.

Noting differences in the racial composition of means-tested program beneficiaries as compared to more universal programs, the authors emphasized the significant possibility that these burdens become “racialized” and exacerbate racial inequality.[112] Ray, Herd, and Moynihan observed that policy makers can legitimize the burdens social welfare beneficiaries face by leaning on concerns about program integrity and fraud.[113] Using colorblind limits and highlighting fraud in means-tested programs are understood by most to be racial dog-whistles, with corruption being a “seemingly colorblind legitimation for administrative burdens that hit Black Americans hardest.”[114] Additionally, the authors asserted that many burdens in the social welfare context are “enhanced” in the context of high-level agency discretion, severing rules from formal “organizational practice.”[115]

The IRS policy of denying prisoners the right to receive immediate cash assistance is, on the surface, racially neutral. But the overt neutrality covers a policy that has a significant racial context. As discussed above, COVID-19 has a disproportionate impact on people of color; with significant racial and ethnic disparities in our nation’s prison system, the IRS’s approach was not racially neutral in impact.

First, consistent with the racialized burdens framework, there was a decoupling of policy from formal agency rules. While the IRS published its position on prisoner ineligibility, as the Inspector General noted and as discussed above, the IRS reversed its earlier decision and did not disclose, either internally or to the public, why it changed its view. The IRS announced the policy that reversed its initial decision only through an informal online announcement in the form of an FAQ.[116] The posting only offered a conclusory statement. The IRS failed to explain why it reached this decision or offer any link to other agency actions that may have offered a rationale.

Second, the IRS’s actions, both before and after the Scholl litigation, diminished the prison population’s agency by imposing burdens that were difficult or impossible to satisfy.[117] For example, even prior to the IRS’s policy reversal, for many incarcerated individuals, including those who may not have filed tax returns in 2018 or 2019, there was no ready access to apply for benefits. Internet access is restricted in prisons,[118] and the IRS did not create or distribute a simplified application process for those who did not have information on file with the agency. Additionally, in the Scholl litigation, the IRS explained that its policy of restricting access to EIPs did not foreclose prisoners from claiming benefits if they filed a 2020 federal income tax return in 2021. That policy would have required prisoners not only to spend time gaining the expertise necessary to complete a tax return but also to subject any refund attributable to the benefit to offset past taxes and other debts.[119] The difficulties prisoners faced following the litigation reveal the ways in which interposing burdensome requirements diminishes their agency. As discussed above, the IRS failed to process thousands of applications in 2020; had difficulty notifying the prison population of its right to claim benefits; and provided no direct, simplified way for the population to access benefits once the court concluded (and the IRS conceded) that prisoners were entitled to receive EIPs.[120] By the fall of 2020, when the Scholl litigation ended, the IRS had already cost the prison population six months’ worth of money they should have received. The burdens prisoners faced to access that money compounded costs and led many to still be without access to the cash they would have received had the IRS not improperly excluded them from eligibility in the spring.

Third, while the Scholl litigation highlighted the IRS’s failure to offer any contemporaneous explanation for its decision, the government offered a general defense based on attenuated concerns with program integrity. This is consistent with the racialized burden perspective, which emphasizes that policy makers may overtly identify integrity or fraud as a rationale to impose burdens that ostensibly allow the government to distinguish between eligible and ineligible recipients.[121] This concept should be less directly tied to the IRS’s actions in Scholl; after all, Congress provided an almost universal eligibility for tax-based pandemic relief. While the IRS and Congress have legitimately targeted tax fraud associated with the incarcerated population in the past—especially around schemes where prisoners (or prison personnel) claimed tax credits that were dependent on the presence of earned income[122]—the IRS did not offer fraud as an ex ante justification for its actions in Scholl. Simply put, the fraud card was not plausibly available, but that did not stop the government from trying. The district court, however, rebuked the justification when it found the IRS’s actions were arbitrary and capricious under the APA.[123]

What lessons can be gleaned from the IRS’s administered COVID-19 relief for the incarcerated? For tax administration to be a force for racial justice, rather than a tool that exacerbates inequalities, Treasury and IRS officials must take concrete steps. This Section describes two of those steps.

One troubling part of the above story is how the IRS communicated its changed position. As discussed, while the IRS initially distributed aid to thousands of prisoners, it announced its changed position online in the form of an FAQ. This form of advice was not unique to the issue. In fact, the IRS has frequently used this method of informal advice in recent years, and it has done so heavily during the pandemic as a way to quickly deliver information to the public and practitioners alike.[124] The practice has drawn criticism[125] with concerns centering on taxpayers’ inability to rely on the IRS’s positions expressed in FAQs, especially for possible penalty relief; the IRS’s practice of changing positions in FAQs without notice; and the related problems of taxpayer and practitioner difficulty in locating FAQs given their lack of publication in more formalized IRS bulletins.[126]

The Scholl litigation highlights other problems as well. The IRS effectively used the FAQ process to announce a legal conclusion that denied prisoners their legal right to benefits. This conclusion was, as the district court concluded, effectively a final agency action that is typical of more formal guidance issued after a transparent notice and comment process.[127] The need for emergency relief may have justified the prompt release of information without a time-consuming notice and comment process. But the IRS’s failure to transparently explain, or at least link other possible explanations for its position, allowed the IRS to proceed in a manner that was impossible to justify given Congress’s clear statutory mandate to deliver benefits to all “eligible individuals”—a class that did not exclude on the basis of incarceration.[128]

Former IRS Chief Counsel Michael Desmond, who discussed the use of FAQs days after resigning from his position, explained that, although the agency practice is criticized, the IRS is likely to continue using this medium to deliver substantive advice, especially when there is a pressing need for quick guidance.[129] While Desmond minimized the risk that taxpayers could be subject to penalties for taking positions in an FAQ, he embraced the need for transparency by better indexing and permanently archiving prior versions of FAQs, particularly given the need to deliver quick information to taxpayers and practitioners.[130]

Desmond’s acknowledgment that the IRS needs to improve the transparency of the FAQ process is important but does not go far enough.[131] There are specific risks associated with agency exercise of informal discretion that will likely exist even if the IRS were to improve the process as Desmond signals. The risks of expressing a categorical legal denial of benefits based on an unstated legal rationale is troubling in a democratic society where the public’s understanding of the tax law “is an essential feature of democracy.”[132] The absence of transparency inhibits public debate and accountability, two attributes of democratic governance.[133]

Scholars evaluating social benefit programs have noted the risks associated with informal agency interactions, though often the focus is on informal front line agency employee interactions that escape meaningful accountability.[134] As Ray, Herd, and Moynihan discuss, when government employees informally exercise discretion, that informal exercise of power can disguise policies that have an outsized negative impact on minorities.[135] While an FAQ differs from a frontline bureaucrat in a traditional social benefit program who may have considerable leeway when making an eligibility determination, we should be especially wary of informal guidance on issues that pose the greatest impact on those with little power to engage the tax system generally. This is especially resonant if the IRS is administering a program like the CARES Act—when its informal, substantive legal guidance had the practical effect of delaying and denying EIPs to those who have little or no power and who are disproportionately racial minorities.

How should the IRS balance its responsibilities, especially when Congress tasks it with an emergency role requiring quickly implemented actions? In critiquing the IRS’s practice of issuing informal substantive guidance adverse to taxpayer positions, especially when taxpayers are less sophisticated and less likely to be in a position to challenge the IRS, Professors Joshua Blank and Leigh Osofsky suggested the IRS “red-flag” its advice.[136] Insinuating the IRS should highlight when its informal positions mask underlying ambiguity, they recommended the IRS disclose or make available the analysis underlying legal simplifications and identify other reasonable interpretations of the tax law.[137]

To be sure, Leigh and Osofsky focused on flagging ambiguous issues rather than issues that appear to be based on policy choices untethered to the statutory language, as is the case with the IRS’s decision to deny EIPs to the incarcerated. Yet by requiring the IRS to at least provide access to its legal justification, the red flagging suggestion may have an in terrorem effect and prevent the government from acting in a disguised effort to harm those with less power—who, in this case, happened to disproportionately be people of color.

In sum, it may be that the IRS should continue to use informal guidance like the FAQs and developments posted on its website. However, when that advice contains substantive legal conclusions, especially when likely to impact on those who are less able to discern the merits of the position, the IRS should do more than post a blanket legal conclusion. It should provide access to an explanation for its position.

In discussing racialized burdens, Ray, Herd and Moynihan emphasized how administrative burdens can exacerbate existing inequality.[138] In the case of EIPs, the most visible burdens arose in the form of an outwardly legitimate rule that immediately harmed prisoners and placed them at risk of punishment if they sought benefits that the IRS claimed they were not entitled to receive. Yet the burdens continued after the Scholl victory. While the government reconsidered close to 386,000 previously incarcerated individuals’ eligibility, made payments of over $465 million, and withdrew its request that approximately 950,000 individuals return their EIPs, there were still significant barriers preventing many from receiving access to the EIPs Congress had earmarked for emergency pandemic relief.

While the victory provided necessary relief for many, prisoners still faced formidable learning and compliance costs that limited or prevented them from receiving legally required benefits. Status reports indicated prisoners were not adequately informed of their rights (although some of that was due to prison officials), and incarcerated individuals faced significant costs when trying to reach the IRS by telephone. The IRS, either on its own or with prison officials, did not make available an efficient way to process payment requests among the many thousands of prisoners who did not have a 2018 or 2019 tax return on file. Adding insult to injury among the lucky prisoners who were able to mail a paper tax return in 2020, the IRS had no mechanism to process those returns. Given the statutory deadline of December 31, 2020, the effect was that, for many prisoners, they and their families would only receive benefits in late 2021. Even then, the statute’s structure meant that the later payment may have been offset for other liabilities, which differed from the first round of EIPs that could only be offset against past due child support.[139]

What could the IRS have done? An agency that seeks to minimize the impact of burdens should have been proactive and considered the burdens differing populations were likely to experience.[140] This means taking a holistic approach to differing populations, anticipating the burdens they might experience, and working to ensure those burdens are reduced or minimized. At times during the pandemic, the IRS attempted to do this (as typified, for example, by its unprecedented working with community groups to deliver EIP information in over thirty-five languages),[141] but it failed with the prison population.

To be sure, the IRS might respond that it was acting in an emergency environment, on a relatively lean budget, and with its employees also facing the pandemic. The IRS had to make difficult resource decisions, and ensuring the prison population could access the funds they were entitled to receive was lower on its priority list than other populations.[142] The insights of Ray, Herd, and Moynihan suggest, however, that the impact of burdens differ greatly by group, and if the IRS wishes to overcome racial disparities, it should be mindful of the racial composition of taxpayer groups facing barriers that prevent access to this emergency relief. While the IRS Commissioner testified before Congress that the IRS was “taking every step to reach potential EIP recipients” and making “extensive outreach efforts into the historically underserved communities[,]”[143] its actions materially harmed the prison population—a group that has traditionally been subject to racial disparities. Rather than being part of the solution, the IRS exacerbated these disparities.

A recent study from the Pew Research Center sought to explore whether people feel the COVID-19 pandemic presents a learning opportunity for Americans.[144] Based on survey data collected by the Pew Research Center, 86% of Americans felt there was some kind of lesson or set of lessons for humankind to learn from the pandemic. Due to variations in responses, the study did not attempt to identify all of the lessons, though one theme Pew noted was society’s failure to address problems like racism and inequality.

Unsurprisingly, none of Pew’s published responses addressed lessons for tax administration. This Article highlights tax administration’s relationship to inequality and race. The IRS’s ostensibly race-neutral decision to deny emergency relief to the nation’s prisoners had a disproportionate impact on people of color. As discussed, the IRS’s decisions can reinforce patterns of racial inequality even in the absence of rules that overtly identify people of color for adverse treatment.

One puzzling part of the story presented in this Article is that the IRS did not contemporaneously explain its decision to reverse its position on prisoner eligibility. While the district court saw its integrity explanations as impermissible post hoc rationalization, we do not know if the decision came from above the IRS—that is, from the Department of the Treasury or others within the Trump Administration. This failure to explain exacerbates the situation and suggests that an improper motive may match the disparate racial impact.

Despite the unknown reasons for the IRS’s actions, well-intentioned tax administrators who want to help society overcome problems of racial injustice must view their work through a prism that includes the impact of the agency’s actions on people of color. Only through awareness is it possible to begin thinking about tax administration as a tool to help overcome our nation’s deep and varied racial justice challenges. That awareness can also help prevent administrators who may be less inclined to use their powers for good. I hope this Article is a small step in that direction.

* Professor of Law, Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law. I would like to express appreciation to my Research Assistants, Anna Gooch, Olivia Arasim, and Joseph Thomas. Thanks also to Keith Fogg, Nina Olson, and Margot Crandall-Hollick for their helpful comments, and to Yaman Salahi, of Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein, co-counsel for the plaintiffs in the Scholl litigation discussed herein. Yaman patiently described the challenges his clients faced and continue to face when interacting with the IRS. Yaman and his colleagues at Lieff Cabraser and co-counsel at the Equal Justice Society deserve special recognition for the excellent advocacy they provided in this case. I would also like to acknowledge all those working to achieve racial justice in the nation’s carceral system, especially those who have dedicated their lives at the grassroots level. All errors are mine alone.

. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020) (codified at 15 U.S.C. §§ 9001–9080). ↑

. I.R.C. § 6428(a)–(c). This provision authorized a payment of up to $1,200 (or $2,400 for eligible individuals filing a joint return), plus $500 for each qualifying child. The amount of the credit may be adjusted and eventually phased out based on an individual’s adjusted gross income. § 6428(c). ↑

. See § 6428(a). ↑

. § 6428(f)(1), (f)(3)(A). ↑

. § 6428(f)(1) (tying eligibility to information in the 2019 tax return); § 6428(f)(5)(A) (allowing the IRS to use 2018 tax information to determine eligibility and amount in the absence of a 2019 tax return). ↑

. § 6428(f)(5)(B). ↑

. I.R.S. News Release IR-2020-69 (Apr. 10, 2020). ↑

. Charles P. Rettig, Comm’r, Internal Revenue Serv., Written Testimony Before the House Oversight and Reform Committee Subcommittee on Government Operations on IRS Operations and COVID-19 Relief (Oct. 7, 2020) (transcript available at https://docs.house.gov/

meetings/GO/GO24/20201007/111085/HHRG-116-GO24-Wstate-RettigC-20201007.pdf [htt

ps://perma.cc/GG3A-NPMB]) [hereinafter Rettig Testimony]. It worked well enough that, in December 2020, as the country continued to suffer from the pandemic, the federal government authorized a second round of EIPs through the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021. § 6428(a). While details about the second round of legislation are outside the scope of this Article, there were key differences, including that the maximum EIP from the second round was significantly less than that of the first. Eligible individuals could only receive $600 ($1,200 in the case of married individuals), plus $600 for each qualifying child. Id. Individuals who believe they are entitled to receive more under § 6428 than they received in either the first or second round of EIPs must apply for a Recovery Rebate Payment when filing a tax return for 2020. See Recovery Rebate Credit, IRS (Feb. 8, 2021), https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/reco

very-rebate-credit [https://perma.cc/Q6U4-GKKC]. ↑

. There were others as well. One involved the IRS’s initial decision to limit the time for non-filers—who were federal beneficiaries—to enter information about their dependents on the IRS’s non-filer portal. See Michelle Gustafson, New Data Reveal How Many Poor Americans Were Deprived of $500 Stimulus Payment for Their Children, Wash. Post (June 30, 2020), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/06/30/new-data-reveal-how-many-poor-americans-were-deprived-500-stimulus-payment-their-children/ [https://perma.cc/AS95-UYUP]. The IRS did not allow federal beneficiaries to add information about dependent eligibility, resulting in a lawsuit claiming the IRS’s actions were arbitrary and capricious under the Administrative Procedure Act and violated the beneficiaries’ Fifth Amendment due process rights. Complaint for Injunctive and Declaratory Relief at 4, McGruder v. Mnuchin, No. 2:20-cv-03590 (E.D. Pa. filed July 22, 2020). The Department of Justice, on behalf of the federal government, settled the case and eventually allowed the federal beneficiaries to enter information that would allow them to receive their full amount of entitled COVID relief. See Michelle Singletary, IRS Reverses Course, Will Send Payments to Low-Income and Disabled Parents Who Didn’t Get $500 for Their Children, Wash. Post (Aug. 14, 2020), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/08/14/stimulus-check-payment-dependent-children/ [https://perma.cc/R9E8-7H4U]. Other challenges related to domestic violence victims who had their EIPs taken by abusive partners—a problem the IRS knew about but failed to address. See Nina Olson, Where There Is a Will, There Is a Way: Economic Impact Payments for Victims of Domestic Violence and Abuse—Part I, Procedurally Taxing (Nov. 4, 2020), https://procedurallytaxing.com/where-there-is-a-will-there-is-a-way-economic-impact-payments-for-victims-of-domestic-violence-and-abuse-part-i/ [https://perma.cc/Y2VP-R8B3]. ↑

. Class Action Complaint at 13, Scholl v. Mnuchin, No. 3:20-cv-05309, 2020 WL 4464896 (N.D. Cal filed Aug. 1, 2020). The exact size of the nation’s vast prison system is unknown, though a 2020 study from the Prison Policy Initiative estimated there are almost 2.3 million individuals across thousands of federal, state, and local prisons and jails. Wendy Sawyer & Peter Wagner, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020, Prison Pol’y Initiative (Mar. 24, 2020), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html [https://perma.cc/HH33-XE6V] (providing a detailed analysis of where and why individuals are incarcerated, including how many are incarcerated by punitive responses to minor non-violent offenses). Many prisoners are held for nonviolent offenses or are detained or incarcerated due to an inability to pay monetary fees or meet bail. See Fines, Fees, and Bail: Payments in the Criminal Justice System That Disproportionately Impact the Poor, Council of Econ. Advisers Issue Brief (Dec. 2015), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/1215_cea_fine

_fee_bail_issue_brief.pdf [https://perma.cc/F25L-GK4Z] (discussing the regressive impact of penalties and their contribution to high rates of incarceration). The Scholl plaintiffs sought and received class certification that essentially included all persons held in custody in federal, state, and local jails, prisons, or other correctional facilities who otherwise satisfied the eligibility requirements under I.R.C. § 6428, including U.S. citizenship, from the date of the CARES Act’s enactment to the date of the lawsuit’s filing. Class Action Complaint at 12–13, Scholl, 2020 WL 4464896; Scholl v. Mnuchin, No. 20-cv-05309, 2020 WL 5702129, at *25 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 24, 2020). In the complaint, the plaintiffs’ counsel noted the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Prisons’ statistics indicated that, in 2018, there were 1,465,158 individuals imprisoned in the United States, with over 90% being U.S. citizens. Class Action Complaint at 13, supra. If there were approximately 1,300,000 individuals otherwise eligible to receive the $1,200 EIP, the total amount at issue in the litigation was over $1.5 billion. Id. ↑

. Treasury Inspector Gen. for Tax Admin., Interim Results of the 2020 Filing Season: Effect of COVID-19 Shutdown on Tax Processing and Customer Service Operations and Assessment of Efforts to Implement Legislative Provisions 4 (June 2020), https://www.treasury.gov/tigta/auditreports/2020reports/20204604

1fr.pdf [https://perma.cc/VV64-V2V9] [hereinafter TIGTA Report]. ↑

. Id. at 4–8. ↑

. Id. at 4, 6. ↑

. Id. at 5. ↑

. Id. The TIGTA Report discusses the mechanism used by the IRS to ensure that the agency within the Department of the Treasury—the Bureau of Financial Service—did not continue paying EIPs to those who were incarcerated, which included temporarily coding payments that were subject to offset for delinquent child support as a way to identify payments that should not be made. Id. The TIGTA Report notes the code actually prevented payment to an incarcerated individual’s spouse, an unintended consequence and additional source of harm. Id. A later status report the government filed in the Scholl v. Mnuchin litigation explored the reach of the IRS’s action and explained how the IRS was able to stop payments to incarcerated individuals through its internal database, which was created with information obtained in October of 2019 from the Federal Department of Prisons and state departments of correction. Fourth Declaration of Kenneth C. Corbin at 2–3, Scholl, 4:20-cv-05309. ↑

. TIGTA Report, supra note 11, at 5–6; see Rebecca Boone, Inmates Got Virus Relief Checks, and IRS Wants Them Back, Associated Press (June 24, 2020), https://apnews.com/article/0810bb67199c9cef34d4d39ada645a92 [https://perma.cc/M2NY-47

49] (detailing the IRS’s efforts to work with state correction departments and return checks issued to the incarcerated); Fourth Declaration of Kenneth C. Corbin, supra note 15, at 3. The IRS later estimated approximately 153,000 incarcerated individuals provided enough information to generate an EIP, through either a filed and processed 2018 or 2019 federal income tax return or through the entry of information on the IRS’s non-filer portal. Id. ↑

. TIGTA Report, supra note 11, at 5. ↑

. Class Action Complaint, supra note 10, at 4 (explaining the IRS’s website reads: “A Payment made to someone who is incarcerated should be returned to the IRS by following the instructions about repayments”); TIGTA Report, supra note 11, at 6 (“Individuals who received a direct deposit payment in error that was not returned to the IRS by the bank were instructed to submit a personal check or money order for the payment amount, notate the check as an EIP along with their Taxpayer Identification Number, and mail the check with a short note to the IRS at a specified address based on where the individual lives. Individuals who received a paper EIP check in error were instructed to return the voided check with a short note to the IRS at the address provided based on where the individual lives.”).

Advocates and commentators quickly noted the IRS’s position was inconsistent with the law. See, e.g., Patrick Thomas, Analyzing the FAQ on Incarcerated and Nonresident Taxpayers, Procedurally Taxing (May 12, 2020), https://procedurallytaxing.com/analyzin

g-the-irs-faqs-on-incarcerated-and-non-resident-taxpayers/ [https://perma.cc/7UKQ-CA84] (identifying the IRS’s position in the FAQ as “flat wrong” and speculating that it may have mistakenly adopted the view to prior stimulus legislation that effectively excluded the incarcerated). The explanation that it was an innocent mistake is inconsistent with the TIGTA Report’s findings. See TIGTA Report, supra note 11, at 4–5. ↑

. Class Action Complaint, supra note 10, at 15. Factual information about Mr. Scholl and Ms. Strawn is found in the complaint. Id. at 2–3. Mr. Scholl resided at Salinas Valley State Prison and was due to be released in November of 2021. Id. at 2. Ms. Strawn had been incarcerated at San Quentin since February 15, 2018 and was released on July 14, 2020. Id. at 3. Neither Mr. Scholl nor Ms. Strawn received their EIPs. Id. at 2–3. ↑

. Id. at 2. ↑

. Id. at 3. ↑

. Order Granting in Part and Denying in Part Motion for Summary Judgment and Denying Motion for Stay at *1, Scholl v. Mnuchin, No. 20-cv-05309, 2020 WL 6065059 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 14, 2020), appeal dismissed, Scholl v. Mnuchin, No. 20-17077 (9th Cir. Dec. 11, 2020) [hereinafter Order Granting in Part]. One striking aspect of Scholl is how quickly the case moved from filing to the September granting of a preliminary injunction, to the October decision in favor of the plaintiffs on the merits, and to the government fully conceding and withdrawing its appeal to the Ninth Circuit by late November. The speed of resolution and striking rebuke perhaps suggest the judiciary and its ability to apply the APA to evaluate the IRS’s actions provide an effective check on potential IRS abuses. The prompt review in Scholl likely would not have been allowed if the tax provision at issue was not structured as an advanced payment of credit, as was the case with the pandemic relief, due to the Anti-Injunction Act (AIA), codified at I.R.C. § 7421. See Stephanie Hunter McMahon, Pre-Enforcement Litigation Needed for Taxing Procedures, 92 Wash. L. Rev. 1317, 1320 (2017) (exploring how the AIA’s prohibition of suits “restraining the assessment or collection of tax” means taxpayers can generally only bring an APA-based challenge to the IRS’s rulemaking in enforcement proceedings, such as in a deficiency case in Tax Court or in a refund suit in the Court of Federal Claims or federal district court). But see Kristin E. Hickman & Gerald Kerska, Restoring the Lost Anti-Injunction Act, 103 Va. L. Rev. 1683, 1756–58 (2017) (arguing Congress did not intend for courts to interpret the AIA as precluding judicial review of pre-enforcement challenges to IRS rules and regulations). The scope of the AIA, and whether it restrains judicial challenges to IRS rulemaking, is raised in a case pending before the Supreme Court. CIC Servs., LLC v. I.R.S., 925 F.3d 247 (6th Cir. 2019), cert. granted, No. 19-930 (U.S. May 4, 2020). ↑

. In Scholl, the government raised numerous procedural defenses, including standing, ripeness, and sovereign immunity, as bases for claiming the court did not have subject matter jurisdiction. The district court rejected those arguments. Scholl, 2020 WL 6065059, at *8–11. ↑

. See Steve Dubb, Families of Prisoners Pay Billions Each Year to Support Loved Ones, Nonprofit Q. (Dec. 19, 2019), https://nonprofitquarterly.org/families-of-prisoners-pay-billions-each-year-to-support-loved-ones/ [https://perma.cc/A4WM-LYR2]. As individuals are increasingly asked to pay for expensive goods and services for their imprisoned relatives, the denial of emergency cash assistance to the incarcerated likely had a multiplier effect, harming not only those behind bars but also innocent spouses and minors. ↑

. See Ashley Nellis, The Sentencing Project, The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons 4 (2016); Infection and Mortality by Race and Ethnicity, The COVID Tracking Project, https://covidtracking.com/race/infection-and-mortality-data [https://perma.cc/52F5-JMYJ]. ↑

. That apathy has been widely noted. For more on its persistence, see Tony N. Brown et al., “Who Cares?”: Investigating Consistency in Expressions of Racial Apathy Among Whites, 5 Socius, May 2019, at 1, 8–9. For a synthesis of research on racism across multiple disciplines, including subdisciplines within psychology, see Steven O. Roberts & Michael T. Rizzo, The Psychology of American Racism, 76 Am. Psych. (forthcoming 2021). ↑

. To be sure, I find tax administration fascinating. Not all do. See Lawrence Zelenak, The Great American Tax Novel, 110 Mich. L. Rev. 969, 978–80 (2012) (discussing the late David Foster Wallace’s unfinished novel, The Pale King, and how Wallace used IRS employees’ tasks to explore the theme of boredom). Zelenak, while a fan of Wallace and a fellow tax law professor, does not fully embrace Wallace’s views that a tax auditor’s job would be tedious. Id. ↑

. See Kristin E. Hickman, Administering the Tax System We Have, 63 Duke L.J. 1717, 1729–30 (2014) (discussing the increasingly important role the IRS plays in policies like housing, health care, and poverty relief). ↑

. As Professor in Residence at the IRS in 2019, I served as co-lead author of the National Taxpayer Advocate’s Special Report to Congress, along with Margot Crandall-Hollick and a team of talented and dedicated employees of the Taxpayer Advocate Service, which was led by then-National Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson. In that report, drawing heavily on the work Nina Olson had previously done, we recommended as an initial principle that the IRS should explicitly adopt its role as a benefits administrator in its mission statement. Nat’l Taxpayer Advoc., 3 Special Report to Congress 4–7 (June 20, 2019), https://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/JRC20_Volume3.pdf [http

s://perma.cc/2QGT-DDP3].

Other scholars have addressed the IRS’s increasingly important role as a deliverer of benefits. See W. Edward Afield, Social Justice and the Low-Income Taxpayer, 64 Vill. L. Rev. 347, 391 (2019) (persuasively linking the work of tax administration to broader issues of social justice that are often more directly associated with non-tax social benefit programs); Michelle Lyon Drumbl, Tax Credits for the Working Poor: Calling for Reform (2019) (providing a comprehensive review and analysis of how the IRS can improve administration of the EITC); Susannah Camic Tahk, Converging Welfare States: Symposium Keynote, 25 Wash. & Lee J. C.R. & Soc. Just. 465, 465–66 (2019) (comparing tax-based benefits, like the Earned Income Tax Credit, to social welfare benefits administered in traditional means-tested programs and noting that tax provisions enjoy broader support and, at times, additional protections for individuals as compared to those other benefits). ↑

. That relationship is not new to all scholars. The foundational work of Professor Dorothy Brown reflects a longstanding interest. See Dorothy A. Brown, The Marriage Bonus/Penalty in Black and White, 65 U. Cin. L. Rev. 787 (1976); Dorothy A. Brown, Race, Class, and Gender Essentialism in Tax Literature: The Joint Return, 54 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1469 (1997); Dorothy A. Brown, Split Personalities: Tax Law and Critical Race Theory, 19 W. New Eng. L. Rev. 89 (1997); Dorothy A. Brown, Racial Equality in the Twenty-First Century: What’s Tax Policy Got to Do with It, 21 U. Ark. Little Rock L. Rev. 759 (1999); Dorothy A. Brown, The Marriage Penalty/Bonus Debate: Legislative Issues in Black and White, 16 N.Y.L. Sch. J. Hum. Rts. 287 (1999); Dorothy A. Brown, Race and Class Matters in Tax Policy, 107 Colum. L. Rev. 790 (2007); Dorothy A. Brown, Race, Class, and the Obama Tax Plan, 86 Denv. U. L. Rev. 575 (2009); Dorothy A. Brown, Homeownership in Black and White: The Role of Tax Policy in Increasing Housing Inequity, 49 U. Mem. L. Rev. 205 (2018); Dorothy A. Brown, The Whiteness of Wealth: How the Tax System Impoverishes Black Americans—and How We Can Fix It (2021).

Others in the academy have also engaged with these issues. Professor Francine Lipman has been a leader of raising racial consciousness in the legal academy with her speaking, advocacy, and writing on the need for tax academics to take a firm anti-racist position in scholarship. See Francine Lipman et al., US Tax Systems Need Anti-Racist Restructuring, 168 Tax Notes Fed. 855, 862 (2020); see also Palma Joy Strand & Nicholas A. Mirkay, Racialized Tax Inequity: Wealth, Racism, and the U.S. System of Taxation, 15 Nw. J.L. & Soc. Pol’y 265, 265 (2020) (contextualizing the anti-tax shift in the United States to racial issues); Camille Walsh, Racial Taxation: Schools, Segregation, and Taxpayer Citizenship, 1869–1973 (2018) (providing a historical review of how tax policy and taxpayer identity are intertwined with white supremacy).

For a contrast between the government’s lack of prosecuting mostly white individuals who engage in tax evasion and the police’s brutal mistreatment of Black men, see Steven Dean, The Truth About Taxes: George Floyd Died, Donald Trump Got Millions, The Crisis Mag. (Oct. 26, 2020), https://www.thecrisismagazine.com/single-post/2020/10/22/the-truth-about-taxes-george-floyd-died-donald-trump-got-millions [https://perma.cc/AL8J-LKWY] (highlighting that the “monstrous injustice deaths of Eric Garner and George Floyd for alleged petty offenses while billionaires flout the law with impunity can be traced to a systematic effort by Republicans to dismantle the IRS”). See also Alice Abreu & Richard Greenstein, Rebranding Tax/Increasing Diversity, 96 Denv. U. L. Rev. 1, 1 (2018) (examining the lack of diversity within the tax bar and suggesting the failure to appreciate the importance of tax laws to other policy objectives outside of raising revenue has contributed to a lack of diversity among tax professionals).

Tax scholars who have applied a critical tax theorist approach have also examined the ways in which substantive tax laws impact taxpayers differently along racial, gender, and class lines. See, e.g., Anthony C. Infanti & Bridget J. Crawford, Introduction to Critical Tax Theory: An Introduction (Anthony C. Infanti & Bridget J. Crawford eds., 2009). Outside of the legal academy, tax scholars are also recognizing the need to embrace race in their research. See William G. Gale, President, Nat’l Tax Ass’n, Presidential Address at the National Tax Association Annual Meeting (Nov. 19, 2020) (calling tax scholars in the field of economics to engage issues of race in research). ↑

. See, e.g., Paul Kiel & Hannah Fresques, Where in The U.S. Are You Most Likely to Be Audited by the IRS?, ProPublica (Apr. 1, 2019), https://projects.propublica.org/graphics/

eitc-audit [https://perma.cc/N7X6-TJQ4] (noting that the counties in the United States with the highest audit rates are predominantly African-American, located in the deep south, and home to a significant number of taxpayers claiming the Earned Income Tax Credit). The IRS has responded to this criticism by emphasizing that the highest income earners (those with incomes in excess of $1,000,000) face higher audit rates than taxpayers claiming refundable credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit. Sunita Lough, IRS Audit Rates Significantly Increase as Income Rises, IRS (Oct. 20, 2020), https://www.irs.gov/about-irs/irs-audit-rates-significantly-increase-as-income-rises [https://perma.cc/2BME-K4UN]. ↑

. By focusing on the IRS, I do not mean to suggest that Congress’s actions should be free from inquiry or criticism. In the CARES Act, Congress explicitly excluded U.S. citizen children from the benefits of emergency cash assistance based solely on the fact that one or both parents were undocumented immigrants. See I.R.C. § 6428(g)(1)(C)(i)–(ii). Working with counsel at Georgetown’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, I have sued the government for its actions, claiming the legislation denies U.S. citizen children of undocumented immigrant taxpayers equal protection of the laws, which is guaranteed by the Constitution. That litigation is ongoing at the time of this Article. See Memorandum Opinion and Order at *8, R.V. et al., v. Mnuchin, et al., 20-cv-1148, 2020 WL 3402300 (D. Md. Jun. 19, 2020) (rejecting the government’s motion to dismiss litigation on procedural grounds). ↑

. I note that, in delivering benefits during the pandemic, the IRS took unprecedented measures to provide information and services to populations it has traditionally not dedicated much attention and resources to. See Terry Lemons, Help Your Community: Partner with the IRS for November 10 “National EIP Registration Day,” IRS (Nov. 5, 2020), https://www.irs.gov/about-irs/help-your-community-partner-with-the-irs-for-november-10-nat

ional-eip-registration-day [https://perma.cc/X5GR-AYHF]; see also Rettig Testimony, supra note 8, at 3. ↑

. See Mario L. Small & Devah Pager, Sociological Perspectives on Racial Discrimination, J. Econ. Persps., Spring 2020, at 49, 52. I am grateful to William Gale, whose speech on race and tax scholarship brought Small and Prager’s work to my attention. Gale, supra note 30. ↑

. See Jeremy Bearer-Friend, Should the IRS Know Your Race? The Challenge of Colorblind Tax Data, 73 Tax L. Rev. 1, 2 (2019) (recommending the IRS collect and publish tax data by race). Professor Bearer-Friend persuasively argues that rejecting colorblindness can help identify and eliminate misperceptions and biases in the tax system. See id. at 45–46, 55. ↑

. Order Granting Motion for Preliminary Injunction and Motion for Class Certification at *26, Scholl v. Mnuchin, No. 20-cv-05309, 2020 WL 5702129 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 24, 2020), perm. app. granted, Scholl v. Mnuchin, No. 20-17077 (9th Cir. Dec. 11, 2020). As I discuss below, the placement of benefits in the federal tax infrastructure raises challenging legal issues—issues the Scholl court directly addressed. See id. at *12–21. In particular, courts have generally allowed the IRS’s actions to escape scrutiny under the APA unless challenged in a traditional tax enforcement proceeding. See, e.g., Kristin Hickman, Coloring Outside the Lines: Examining Treasury’s (Lack of) Compliance with Administrative Procedure Act Rulemaking Requirements, 82 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1727, 1731 (2007). ↑

. Victor Ray et al., Racialized Burdens: Applying Racialized Organization Theory to the Administrative State, SocArXiv (Dec. 9, 2020), https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/q3xb8/ [https://perma.cc/PL3E-R6R8]. ↑

. Class Action Complaint, supra note 10, at 2. The Center for Taxpayer Rights, a nonprofit organization dedicated to furthering taxpayers’ awareness of and access to taxpayer rights that is led by former National Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson, worked with counsel and assisted their efforts throughout the litigation. ↑

. Id. at 7. ↑

. Id. ↑

. I.R.C. §§ 6428(c)–(d). ↑

. Class Action Complaint, supra note 10, at 14–16; § 6428; 5 U.S.C. §§ 702, 706(1)–(2). ↑

. Class Action Complaint, supra note 10, at 5–6, 8. ↑

. Id. at 6. ↑

. Scholl v. Mnuchin, No. 20-cv-05309, 2020 WL 5702129, at *26 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 24, 2020). ↑

. Order Granting in Part, supra note 22, at *3. ↑

. Id. Under Nken v. Holder, in deciding whether to grant a stay, the court must consider: “(1) whether the stay applicant has made a strong showing that he is likely to succeed on the merits; (2) whether the applicant will be irreparably injured absent a stay; (3) whether issuance of the stay will substantially injure the other parties interested in the proceeding; and (4) where the public interest lies.” 556 U.S. 418, 426 (2009) (citing Hilton v. Braunskill, 481 U.S. 770, 770–71 (1987)). ↑

. 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A). The court rejected the plaintiffs’ first claim under the APA: that the IRS was unreasonably withholding or delaying action in violation of 5 U.S.C. § 706(1). In rejecting this claim, the court emphasized the IRS had, in fact, acted and “[w]hat the plaintiffs [were] objecting to [was] not so much the failure to act but the manner in which the IRS decided to stop payments to incarcerated individuals and the legality of its decision to do so.” Order Granting in Part, supra note 22, at *15. ↑

. Order Granting in Part, supra note 22, at *23 (citing Camp v. Pitts, 411 U.S. 138, 142 (1973)). The court also rejected the government’s standing, ripeness, and sovereign immunity defenses, which were offered to delay potential judicial review until after the plaintiffs filed and were denied claims for credit on their 2020 federal income tax returns. See id. at 4–9; see also R.V. v. Mnuchin, 20-cv-1148, 2020 WL 3402300, at *4, *7 (D. Md. June 19, 2020) (rejecting the government’s standing and sovereign immunity arguments in an equal protection challenge to the CARES Act’s statutory denial of EIPs to children born to mixed-status families where the parent, or parents, is not a U.S. citizen). ↑

. Order Granting in Part, supra note 22, at *13. ↑

. Id. at *30 (“[T]he IRS must (subject to other provisions of title 26) refund or credit an overpayment attributable to section 6428 and do so as quickly as possible.”). The court relied on the Second Circuit’s reasoning from a case concerning stimulus payments that were made during the 2008 financial crisis, writing:

[T]he Sarmiento court also found persuasive the fact that the “shall be treated” language in § [6428(f)(1)] . . . . “is best interpreted as establishing the legal fiction that eligible taxpayers overpaid their 2007 taxes in an amount equal to the ‘advance refund’ of their [stimulus payment” . . . . It further reasoned that the “negative conditional phrasing” used in subsection [(f)(2)] “seems to reflect a presumption on the part of Congress that the ‘advance refunds’ available under subsections (f) and (g), in contrast to those available under subsections (a) and (b), do apply to the 2007 tax year.”

Id. at *17 (citing Sarmiento v. United States, 678 F.3d 147, 152 (2d Cir. 2012)). ↑

. Id. at *31. ↑